Pauline Hanson’s political career has been full of ups and downs. After a decade of downs, it seems like Pauline is heading toward some ups. James Eisen analyses Hanson’s political career, the bumps in One Nation, and puts forward the question: where is Hanson going?

Future books on Australia’s political history will likely begin their narrative in 2025. PM Anthony Albanese delivered Labor a historic election victory, smashing all expectations and leaving both the Greens and the Liberals on the ropes. After navigating Australian politics for many years with the skills of a professional gambler, Albanese has finally hit the jackpot and is steering Australia into the twenty-first century. More importantly, perhaps, 2025 was also a year of significant expansion for Australia’s newly revived Right-wing populist movement.

Of course, anti-immigration sentiment is nothing new in Australian history (from Operation Sovereign Borders to the White Australia Policy), but there is now renewed opposition to the long-held consensus on migration. As defined by the major parties, this consensus was built on ‘tough’, telegenic state crackdowns on illegal migrants as a means of securing white suburbia’s support for high levels of legal immigration. A majority of Australians now believe the country is admitting too many immigrants, with a noticeable rise in anti-immigration sentiment even among Australians aged 18-29.

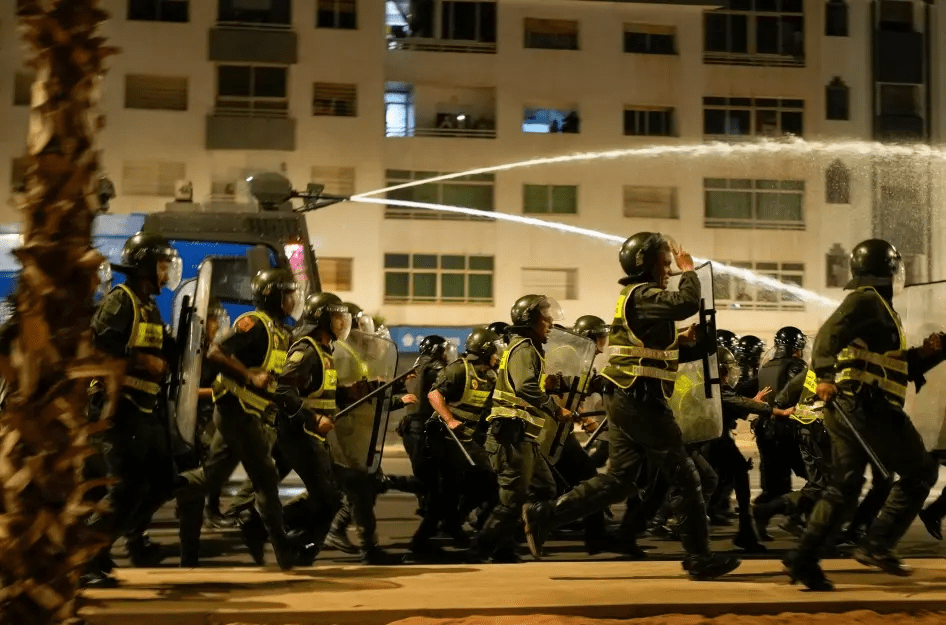

With the Liberals and Nationals paralysed by factional infighting, One Nation has been the primary beneficiary of these recent trends, with Hanson’s once fringe outfit now out-polling the Coalition (the Liberal Party and National Party). The antisemitic terrorist attack on Bondi Beach and Albanese’s confused and muddling response have threatened to turn yet more voters away from our longstanding multicultural consensus. Andrew Hastie, establishment conservatism’s last hope, has so far failed to unseat Sussan Ley and has discredited himself among much of the Right. Even if a conservative eventually topples Ley, One Nation remains on track to win more than a dozen seats at the next election.

As of writing, the Nationals have once again split from the Coalition, leaving the Liberals in even more dire straits. The high-profile defection of Barnaby Joyce seems to have paid off, and if current trends continue, more defections are to be expected. Pauline Hanson, long considered a mere annoyance, now has the opportunity to rewrite Australian politics.

Hanson came to national prominence in the lead-up to the 1996 election, when she was pre-selected and subsequently disendorsed by the Liberal Party for the seat of Oxley, in the ‘middle Australia’ town of Ipswich. Her disendorsement followed controversy and outcry over a letter she sent to the Queensland Times on Aboriginal deaths in custody, in which Hanson rejected any notion of systemic injustice and framed excessive state support as the cause of Indigenous disadvantage.

After protests and media uproar, with Hanson refusing to back down, she was dumped by the Liberal Party, on John Howard’s orders. Despite this, the timing of the election meant Hanson’s name remained on the ballot. Against all the odds, Hanson won the seat with a 19% two-party-preferred swing. The Nationals abstained, the Liberals continued to offer passive support, but above all, her victory was down to her and her ability to rile up disgruntled Labor voters.

In her now infamous maiden speech to Parliament, she bemoaned that Australia was at risk of being “swamped by Asians”. She then established her party, One Nation, which would go on to win 11 seats at the 1998 Queensland election. This was where her popularity peaked. Later that year, Hanson would lose her seat after both major parties preferenced her last, and a redistribution split her electorate in two.

What followed was a familiar pattern: internal division, personalist leadership and organisational incompetence. Hanson’s autocratic control alienated her parliamentary cohort, leading to mass resignations. The New South Wales branch split amid a falling-out with her deputy, David Oldfield. In 2002, amid plummeting support, Hanson resigned as party leader.

The disintegration of One Nation culminated in Hanson’s prosecution for electoral fraud. A former party member successfully argued that One Nation had been fraudulently registered, with party membership consisting of a nominal ‘support group’. The resulting civil suit, funded in part by then backbencher Tony Abbott, saw Hanson prosecuted by the state of Queensland and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment. Though the verdict was later overturned on appeal, Hanson had already spent eleven weeks in jail. By the mid-2000s, Hanson was a marginal figure. Without a party or a seat, she became a mere curiosity in Australian political history.

Her eventual return owed more to persistence than learning. After a decade of failed campaigns, Hanson rejoined One Nation in 2013, reclaimed the leadership, and was elected to the Senate in 2016. Since then, she has remained a fixture of Australian politics, more notorious than powerful, but ever present. For many of the progressive or centrist persuasion, the tale of Pauline Hanson was a stunning success of how “freaking amazing” institutions can avoid the threat of “populism”, aided by our “national treasure” of an electoral system. If only the Weimar Republic had implemented preferential voting, how many lives could have been saved?

The phenomenon of “populism” is really a euphemism for the global political crisis of twenty-first-century capitalism, which erupted in 2008 and was most clearly registered in the twin political candidacies of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders in 2016. Ten years later, Australia now faces what appears to be a choice between Albanese and Hanson, or at least between what Albanese and Hanson represent. Albanese and Hanson, both children of the 1990s, embody the end of Australia’s own neoliberal revolution in particular ways.

Albanese is a career politician whose cautious approach to government was forged in Labor’s years in the wilderness under Howard. Unlike some of his forebears, he has outlived the era of Coalition dominance. Hanson is a race-baiting demagogue who, through sheer tenacity and inertia, has made herself the face of Australia’s nascent post-neoliberal Right. Their nature as figures formed under a now-exhausted order is what marks them as of our moment, as Australia is forced to choose between actively shaping a post-neoliberal order or merely drifting into one.

If Albanese and Hanson are both post-neoliberal in some way, what does neoliberal mean and what would it mean to go beyond it? Neoliberalism was one in a long line of “regimes of accumulation”, distinct social and political arrangements that serve to mediate the necessity of capital accumulation.

For Marx, capitalism was a contradiction between bourgeois social relations and industrial forces of production. That is to say, the social relations of the free exchange of labour and its products are rendered untenable by industrial production, making labour increasingly unnecessary. This leads, for the first time in history, to a problem of large-scale unemployment. This had to be dealt with, and has been dealt with, in a variety of ways. Horkheimer put it more simply, “machines have made not work, but the workers, superfluous”.

The post-war consensus, a uniquely Australian version of Keynesianism, directly preceded neoliberalism. This regime of regulated capitalism, with direct state involvement in the economy, protectionism, immigration restrictions, and generous welfare measures, of course, would not last.

The very conditions that gave rise to Keynesianism made it untenable. Rising labour costs, slowing productivity growth, and increased global competition squeezed profits, while accumulated capital could no longer be profitably reinvested. The tools that had sustained full employment ceased to function, and efforts to stimulate demand now produced inflation and stagnation rather than growth. A new generation found the world of Keynesianism restrictive and one-dimensional. The result was a crisis Keynesianism was structurally incapable of resolving. Neoliberalism promised to solve the problems of Keynesianism by contracting the public sector, removing trade barriers to promote efficiency and economic growth, and using the state to subdue organised labour to keep inflation permanently manageable.

Neoliberalism, too, has proved temporary. Deregulation and financialisation fell out of favour in the 2008 crash, and the rise of China has led to a reconsideration of the domestic and international outcomes of free trade and the offshoring of manufacturing. When the three biggest innovations of neoliberalism; privatisation, technocracy and free trade, have been repudiated from both ‘progressive’ and ‘conservative’ perspectives, it seems we are overdue for another revolution in capitalist politics, to kick the can down the road again, and all the destruction that entails.

This interregnum is nothing if not chaotic. Capitalist politics is no longer delineated by a clear Left-Right spectrum, but instead the old order is arrayed against competing versions of the new. Albanese has been willing to adapt to the post-neoliberal world, accepting a renewed importance of national sovereignty and presenting his own industrial strategy in “A Future Made in Australia”. But Albanese’s progressivism is for a conservative end, and Hanson represents a form of politics which wishes to take renewed initiative in building a post-neoliberal Australia, a conservatism for a progressive end.

It is unclear whether Hanson is up to the task she has set for herself. Her party has long been infamous for infighting, and Hanson lacks the charisma of Trump or the shrewdness of Nigel Farage. Since her election to the Senate in 2016, she has lost no less than 10 members of state or federal Parliament to resignations. It was only in 2025, 28 years after the party was founded, that One Nation finally decided the time was right to roll out a branch structure.

To his credit, her Chief of Staff, James Ashby, appears to grasp what would be required to turn polling momentum into political reality. Ashby has described One Nation as a “centre-right party” and insists that it “isn’t just talking about immigration”. Perhaps a charitable interpretation right now, but Ashby is echoing the strategy of the post-neoliberal Right abroad, to seek not to be a party of protest, but to redefine the political landscape for a new era and replace the old centre-right parties.

Immigration restrictions are, at an economic level, protectionism for blue- and pink-collar labour. This simple demand can and has been expanded into a full program of neo-nationalist governance, as Trump and Farage have done. But Ashby’s moderation collides with the same structural limits that define Hanson’s leadership. How can a decades-old project surrounding one woman become a party of government?

Hanson has also consistently resisted any political talent that could eclipse her or threaten her power. An example of this was when she refused to let former Liberal senator and savvy protectionist, Gerrard Rennick, replace her aging, substandard subordinate, Malcolm Roberts, on her 2025 Queensland Senate ticket. This led Rennick to form his own party in opposition to Hanson. Any competent minor party should be begging for talented defectors, but for Hanson, loyalty is more important than competence when choosing allies. Nonetheless, Hanson’s subpar decision-making hasn’t prevented her from cracking 20%. Rennick and his comrades in the swamp of minor Right-wing parties have been forced to watch from the sidelines as Hanson enters the mainstream.

Further on the margins still are an emerging ecosystem of ‘New Right’ commentators seeking to capitalise on Hanson’s rise. These conservative revolutionaries have no illusions about her capabilities. Former Liberal staffer and self-styled “shaman of Australia’s Radical Right” John Macgowan bluntly describes Hanson and her candidates as possessing “sub-optimal intellectual capability”, but recognises that the recent spike has been due in part to a well-coordinated social media campaign, indicating the beginnings of an “operation that can replicate forecasted performance”.

What Macgowan and many others like him see is that Hanson the woman matters far less than Hanson’s moment. Her rise marks the end of decades of Australian political consensus, creating an opening which those more competent than Hanson, both online and offline, are eager to exploit.

Hanson is not going to become Prime Minister any time soon. Trump’s strategy of appealing to ‘flyover country’ at the expense of urban areas is simply not repeatable down under, since ‘middle Australia’ is not a numerous enough voting bloc, and Hanson’s brand cannot be easily altered towards the goal of winning over urban voters. What Hanson can and will do, however, is manifest a political crisis that Australia has long been able to avoid.

For the last decade, Australian politics, on both the Left and Right, has largely been a matter of coasting along on past success, but now the bill has come due and political innovation is necessary. Will that change come from Albanese, Hanson, or someone else? It is too soon to say. What is now certain, however, is that the question is no longer whether Hanson, but whither Hanson.

You must be logged in to post a comment.