Nineteen years ago, the Tongan capital descended into flames as pandemonium gripped the streets. Mainstream imperialist press peddles narratives of rampant youth gangs destroying peace and order. But under the surface, writes Max J, there was a heightening political struggle which is often overlooked.

The 2006 Riot

The first riots started at 3pm on Thursday, November 16th. The first targets of the rioters were government buildings in the capital city of Nuku’alofa. Then, they moved on to buildings owned by government officials and foreign banks, in particular ANZ and Westpac. Police stood on the sides of streets and watched helplessly as the violence took place, or perhaps they weren’t bothered to stop it. At the Chinatown Hotel, a gang of youths arrive, followed by a quarry truck. Despite the pleas of the hotel’s owners to spare the building, it too is soon torched with firebombs.

All sorts of people participated in the riots: the young, the elderly, men and women. But the more bombastic acts of violence – such as the firebombing, car tipping, the demolitions, were seemingly done primarily by younger men. By the end of the night, most of the capital city had been burnt to the ground. Tongan Police and military were scarcely able to retake control of the capital’s CBD.

Earlier that day, a crowd of several thousand gathered in Nuku’alofa, near Tongan Parliament. The expectation of the crowd was that the nobles, who were guaranteed seats in Parliament, would support parliamentary and electoral reforms which would, among other things, increase the number of seats for people’s representatives (MPs elected by commoners). This did not come to pass. Instead, Tonga’s parliament (Fale Alea ʻo Tonga) adjourned for the year. This angered the crowd. Armed with hammers, sticks, rocks and bricks, they vented their frustrations through the last means available to them: a riot.

On paper, Tonga had been a constitutional monarchy since 1875, when King George Tupou I adopted a modern constitution. Though Tonga had been unified as a single entity since 1845, it wasn’t until the adoption of this constitution that Tonga became a ‘modern’ state. This constitution enshrined a parliamentary style of government that is similar to, but not exactly like, the ‘Westminster system’ developed in England.

This parliament held seats for hereditary nobles, as well as for representatives elected by commoners. While ostensibly upholding the principle of equal representation for nobles and commoners, as it often goes, the nobles and chiefs held most of the power in government. This is not to say that the nobles are, or were, necessarily a monolith, or that they voted as a bloc, since the nobles rarely formed a unified front of their own. But their class position granted them access to power and a proximity to the royal family that allowed them to politically outflank commoners, in parliament and beyond.

The Prime Minister and Cabinet were all appointed directly by the King. This was the case until 2014, when ‘Akilisi Pohiva of the Human Rights & Democracy Movement (which had formed the Democratic Party of the Friendly Islands by that time) was elected PM. The Human Rights & Democracy Movement (HRDM) is a liberal reformist movement, which aimed to reform the Tongan political system to squash corruption and adopt a more liberal-democratic structure which would strip the King of direct executive power.

The Human Rights and Democracy Movement

The HRDM was founded in the 1970s, first as an informal grouping of liberal and democratically minded politicians, lawyers and professionals in Tonga. It was formalised in 1992 as the ‘Pro-Democracy Movement’, and it fielded candidates for the 1999 election. The HRDM/PDM had a political orientation which was never fully coherent. Its members were broadly Christians and Liberal, but did not have a wholly unified view of what kind of democratic system would be best for Tonga. By the 1999 election, its members and leadership included Dr Sione ‘Amanaki Havea (Wesleyan minister and developer of ‘Pacific theology’), Rev. Simote Vea (Wesleyan minister), Fr. Selwyn ‘Akau’ola (Roman-Catholic Priest and editor of the Tongan Catholic monthly Taumu’a Leilei), Prof. Futa Helu (founder of the liberal and independent ‘Atenisi Institute — both a high school and university), ‘Akilisi Pohiva (teacher, radio host, newsletter editor, and long-time democracy advocate), and many others.

While democratic pro-reform candidates won more seats than previously in the 1999 election, they received fewer votes. For example, in 1996, ‘Akilisi Pohiva got 9,149 votes in Tongatapu 1, while in 1999, he got 8,556. Of the nine People’s Representatives elected, five were pro-reform: ‘Akilisi Pohiva, ‘Uliti Uata (HRDM founder), Sunia Fili, Samiu Vaipulu, and ‘Esau Namoa. Their success, despite their fewer votes, is attributed mainly to their style of campaigning. Unlike traditional elections for People’s Representatives, the HRDM/PDM candidates campaigned as a bloc, running awareness campaigns in villages in electorates they intended to run in. However, it is important to note that People’s Representatives, even the more ideologically vocal ones, are mostly elected based on personal factors (familial relationships, etc).

Class in Tonga

Much of the political struggle for democratic reforms is influenced and heightened by class in Tonga. Class stratification in Tonga, and indeed the entire Pacific region, is complex. In Tonga, this involves different forms of social divisions which often overlap, and sometimes contradict each other. There are clans (ha’a) which fall under chiefly titles and estates owned by chiefs and nobles (hou’eiki). Hou’eiki maintain power in Tongan society (past and present) through various means. Their power is consolidated socially through faka’apa’apa (deference/respect). On the one hand, it is a form of social cooperation between peoples that crosses classes. On the other, it is a form of feudal obligation between rulers and the ruled.

Like other indigenous peoples worldwide, Tongan culture has a complex system of kinship. Tongan kinship survived modernisation, though it has changed form over the centuries and decades since. Kinship establishes gender roles, patriarchal authority, and the transfer of property between generations. For example, in Tongan families, control over property is held by fathers and eldest male children/siblings. However, sisters have a higher ‘rank’ in the Tongan system of rank and power than brothers do. This contradicts the fact that the elder brother has more authority in the family/kāinga than the elder sister does. Despite their higher ‘rank’, sisters do not have authority over brothers. While both men and women are respected (faka’apa’apa), men are respected on the basis that they have power and authority, while women are respected on the basis that men have an obligation to care and provide for them.

This speaks nothing to the broader system of social class that developed both before and after capitalism took hold in the Pacific. Families do not tend to cross class lines. Families rarely if ever comprise both commoners and nobles. In the chiefly system, chiefs and nobles (the ‘eiki) ruled over estates, which were territorial divisions including both entire islands, and sections of islands. This class of chiefs and nobles had ruled the islands that made up Tonga for thousands of years. In modern Tonga, the rule of the chiefs and nobles is less extreme, but nonetheless persists in spite of centuries of capitalist modernity.

Prelude and aftermath of the 2006 riot

Politically, Tonga is a strange country. It has an ostensibly democratic (and unicameral) parliament, though it wasn’t until the 2010s that elections actually changed the composition of government. The HRDM campaigned strongly on government transparency, anti-corruption, limiting the power of the monarch, and liberal democratic reforms such as a separation of powers and ‘rule of law’. In 2006, HRDM leaders urged and supported a street protest in Pangai Lahi. This protest was held on June 1st, when Tonga’s parliament opened. This peaceful protest was suppressed by the Tongan state, which then launched fines and legal proceedings against its organisers (‘Akilisi Pohiva, Teisina Fuko, and others), though many pleaded not guilty. If only the monarchist government had the gift of foresight — as the suppression of this peaceful protest only increased tensions which would boil over in November with the riots.

The aftermath of the riots in November 2006 saw the immediate launching of a state of emergency by the royalist government (headed rather reluctantly by Feleti ‘Fred’ Sevele, who had taken over as PM after the resignation of ʻUlukālala Lavaka Ata/future king Tupou VI) which lasted until the early 2010s. The state launched a legal assault against the democracy movement: democratic leaders such as ‘Akilisi Pohiva and others were arrested and charged with sedition in 2007, though these charges did not stick, and Pohiva went on to successfully be elected to the electorate of Tongatapu in the 2008 election.

Almost immediately following the riots, pacific rim imperial forces from Australia and New Zealand entered Tonga — ostensibly to help the government ‘restore order’. 110 soldiers, along with 44 police officers, arrived from AU/NZ to supplement the Tongan police and military (the Australian contingent was comprised of the 1st Battalion RAR). What followed was a little over a month of imperialist terror: both foreign and Tongan police and military rounded up hundreds of protestors and non-protestors alike. Soldiers assaulted everybody, young and old, for as little as drinking alcohol on the street. The imperialists withdrew their forces in December 2006, though the damage had already been done.

The 2008 election was an upswing for the democracy movement, which showed its resilience against the anti-democratic state of emergency. ‘Akilisi Pohiva criticised the continuation of the state of emergency:

“I don’t see any reason for government to continue to hold on to the emergency power. There are a lot of allegations against the Prime Minister and some of the ministers. And I think the government, especially the Prime Minister and the Minister of Tourism, they are under threat and they still have to respond to so many allegations.” (RNZ, 28 January 2008).

While the state of emergency persisted, in 2008 the democratic movement elected six representatives: four from the HRDM, and two from the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). The PDP was formed in 2005, after its founding members were expelled from the HRDM/PDM over disputes around candidacies. It was established at a founding meeting at the ‘Atenisi Institute, and included ‘Atenisi founder Futa Helu. Police Minister Clive Edwards, long hated by the movement for his role in supporting the monarchist government in his capacity as police boss, was also a founding member of the PDP (known as the Tongan Democratic Party in 2005). The PDP was also the first registered political party in Tonga, since the HRDM was not a registered political party. The cracks were beginning to show in the ‘pro-democracy movement’, which was never a single unified force to begin with.

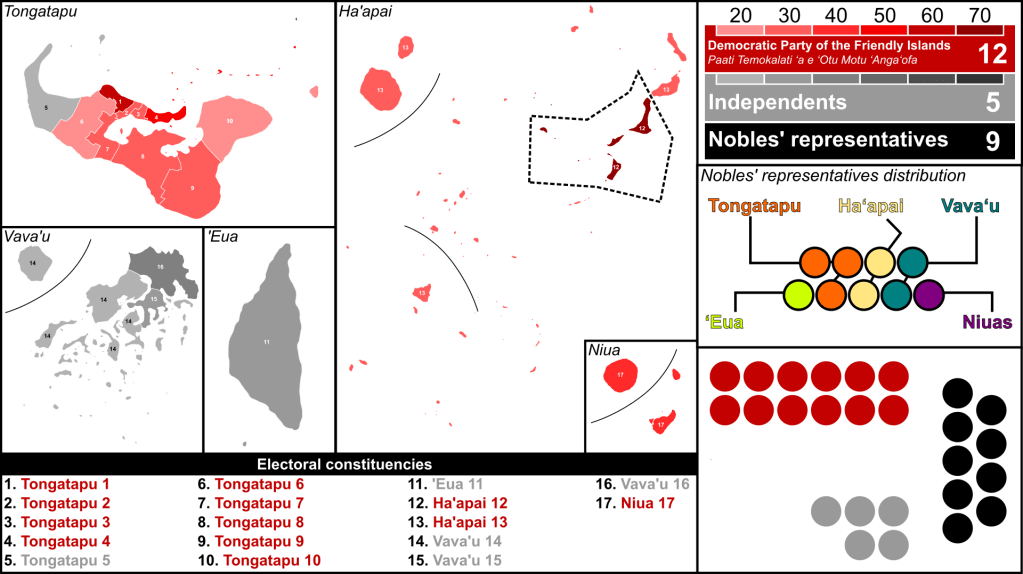

In 2010, democratic reforms were adopted. The number of People’s Representatives was increased from nine to seventeen, giving commoners more representatives than nobles. There were now four political parties: the Democratic Party (founded by the HRDM/PDM), the People’s Democratic Party (now defunct), the Sustainable Nation-Building Party (formed by Auckland-based lawyer Sione Fonua, now defunct), and the Tongan Democratic Labor Party (an attempt at a social democratic party, formed by members of the Public Services Association, seemingly defunct).

The 2010 election had mixed results for the democrats. While the Democratic Party earned less votes than its HRDM parent did in 2008 (partly due to the electoral reforms changing numbers, and new parties running after splits in the movement), it won more seats (as more seats were given to commoners). The People’s Democratic Party, which won two seats in 2008, lost both of these in 2010. However, this election set the stage for the democratic party’s historic win in 2014: when ‘Akilisi Pohiva became the first commoner to be elected PM. Pohiva would govern as PM from 2014 until his death in 2019.

The often overlooked history of Tonga’s democracy movement, as divided as it is, has many lessons for the international socialist movement. It shows that even in countries as deeply conservative as Tonga, there can, and does, exist a (at the very least liberal) reformist current willing to mobilise politically for changes to the system. But, crucially, we must recognise that liberal reformers cannot bring true democratic change, nor lead the workers and toilers to power.

The HRDM/PDM and DPFI (Democratic Party of the Friendly Islands) has waged an admirable struggle for democratic reform in Tonga. However, it has shown itself to be incapable of taking the big steps necessary to establishing a truly democratic system. Most importantly, it is a liberal-bourgeois movement influenced by Christian ministers and intellectuals, who have no interest in abolishing the monarchy or establishing a republic.

The events of 2006 were nothing short of an attempted revolution. It came after decades of political organising by the democratic movement, and historic strikes by public service workers in 2005. The events of November shook the royalists and the nobles to their core, and they worked hard to smash the commoners and restore order, with the backing of their pacific rim imperialist allies in Australia and NZ.

But peace and order are fleeting. It is more than possible for a revolutionary upsurge to take place a second time in Tonga. It leaves open the question of leadership, particularly, revolutionary leadership. Tonga lacks a socialist movement, though the attempt at a social democratic Labor Party may have laid the groundwork for one. With a suffocating political atmosphere marred by suppression and intimidation, it seems likely that the development of revolutionary socialist leadership for the Tongan workers and toilers must develop in exile – amongst the diaspora living in the pacific rim and beyond.

This movement cannot win power from the outside: it must carry out political awareness campaigns and organising drives inside of Tonga, to build the movement domestically. Tonga prides itself on being the last kingdom in the Pacific. With any luck, it may be able to pride itself on being the first democratic republic in the Pacific.

You must be logged in to post a comment.