Stalin’s rise to power in the 1920s is mythologised by much of the Left (both pro- and anti-Stalin) as being inevitable. But, Mila Volkova writes, Stalinism was far from inevitable.

In 1918, the German ambassador to the Soviets is shot and killed by the Bolsheviks’ coalition partners in the Left Socialist Revolutionaries (Left-SRs: a party of intellectuals with the majority support of the poorest peasants). Lenin is shot by a member of the Left SRs, leading to an illness that will eventually kill him. The Left SRs are suppressed. The aristocrats, capitalists, rich peasants, and Mensheviks (reformist socialists) revolt and organise themselves behind the White movement. The Mensheviks are banned. In Germany, sailors mutiny at Kiel, igniting a revolution that topples the German Empire. The newly formed government of the German Republic, made up of Social Democratic politicians, ends its own revolution. To defend their revolution, the Bolsheviks enforce War Communism on the population – the total mobilisation of the working class and conscription of the peasantry into a civil war that kills 7 million people.

In 1919, the German social democrats make use of fascist militias to slaughter revolting German workers. In Austria and Hungary, the Romanian army butchers the newly formed Soviet Republic.

In 1921, sailors and workers mutiny at the Kronstadt naval base, raising contradictory demands, including free elections and the end of the grain requisitions. Fearing French invasion, the Bolsheviks launch an assault to retake the base. In response to growing peasant unrest and strikes, the Bolsheviks respond with both the carrot and the stick. A peasant revolt is put down with mustard gas. Party factions are banned, ending internal democracy. The New Economic Policy (NEP) is implemented, restoring market relations and replacing the grain requisitions with a tax while keeping large businesses under state ownership.

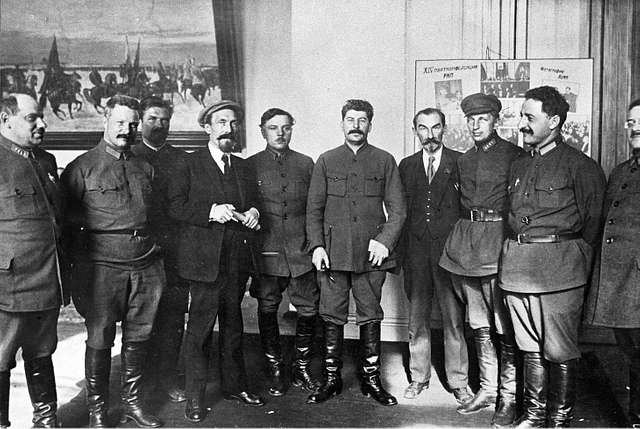

By 1922, the Civil War is over, but internal party elections are practically replaced with top-down appointments by the Central Committee. Joseph Stalin is elected General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

In 1923, Lenin orchestrates the expulsion of more than 100,000 Communist Party members who joined up post-1917, roughly a third of party membership, whom he accuses of careerism. The party divides into three informal factions: the Left (around Red Army commander Lev Trotsky) and the Centre (around Stalin) are opposed to the continuation of the NEP, favouring a class war against the peasants, while the Right (around the editor of Pravda, Nikolai Bukharin) supports the continuation of the worker-peasant alliance. Both the Left and Right oppose an increasingly bureaucratic party led by the centre

In 1924, Lenin passes away. Stalin implements the “Lenin Levy”, recruiting over 500,000 under-educated peasants and workers into the party ranks.

By 1925, industrial growth is lagging, and rich peasants are demanding so much compensation for their grain that an economic catastrophe looms on the horizon.

In 1927, the Left is expelled from the party and public political dissent is prohibited. The final elements of non-Bolshevik socialist political activity are suppressed.

In 1928, the economic crisis reaches a boiling point with peasants refusing to pay the grain tax en masse. The internal right wing of the party is defeated, the NEP is over, and work begins on drafting the first Five-Year Plan.

In 1929, the Five-Year Plan begins. Industrial capacity explodes with a pace never seen before; at the cost of millions of lives lost to a state-orchestrated famine-machine that deprives peasants of grain and forces them into collective farms. Although the last remnants of internal opposition are purged by 1936, the Bolsheviks are already the “monolithic party” of Stalin – an institution of total order and mechanical obedience.

What is the relevance of these dates and events to those of us who remain committed to the communist project? Deciphering their meaning is important for more than just defending ourselves from the rhetorical attacks of anti-communists. In defending ourselves, socialists have a habit of fetishising historical events. But understanding the Bolsheviks is about more that point-scoring: it is about understanding ourselves.

Socialism, as in the abolition of classes and the regulation of production according to a common plan, was obviously not achieved in the USSR. But it was communists who created it. Blaming the international bourgeoisie for the degeneration of the USSR serves no purpose; their inevitably violent response to revolution is a given. Rather, because the USSR is within our historical legacy as communists, even if it was not communism, we must learn from our errors if we want to avoid repeating them. This requires a systematic investigation into the character of Stalinism and the origins of the Soviet Regime. As Bini Adamczaks stated in Yesterday’s Tomorrow about the connection between the Bolsheviks and communists today:

“For them, there will never be any communism. There is no communism for them. There is no communism without them. There will never be any communism without them.”

What Was Stalinism?

To tell the truth they are not directing, they are being directed. Something analogous happened here to what we were told in our history lessons when we were children: sometimes one nation conquers another […]. Here things are not so simple […] the vanquished nation imposes its culture upon the conqueror.

Opening speech in Eleventh Congress of the R.C.P. by V.I. Lenin

The proletariat, possessing nothing of their own and with nothing to lose but their chains, is the subject of communist politics. Recognising that Russia was a majority peasant population, the Bolsheviks held the view that any successful revolution in Russia required a successful revolution in its more industrialised neighbours (Germany in particular). If the revolutionary wave began in Russia, the Bolsheviks took the line that the working class should ally with the peasants most sympathetic to the revolution, end feudalism, establish a state capitalist economy to industrialise the country and proletarianise the peasantry, and wait for rescue.

But that rescue never came. With the USSR surrounded on all sides and the Bolsheviks abandoned by all those it considered allies, they found themselves in an unsustainable position. They could claim the support, at most, 20% of the population. The Civil War made the situation truly desperate. Industrial production collapsed, so the cities emptied out as workers returned to their villages. After the war, around 10% of the population could be considered proletarian. The party itself suffered a manpower crisis, as much of its most experienced members were killed leading as front-line officers in the Red Army.

The gradual development of state-capitalism was replaced with the brute force of War Communism. Without a solid basis for democratic rule (which the Bolsheviks envisioned), but unable to surrender power for fear of being massacred, the Bolsheviks used the only apparatus capable of ruling the country – the old Tsarist bureaucracy, which had not yet been destroyed. Though they had planned to smash it and replace it with direct workers’ control, they instead subordinated it. Thousands of bureaucrats’ families were taken hostage and the Bolsheviks ruled through sheer violent terror against all opponents – real or imagined.

Once the Civil War concluded, this temporary measure was replaced by the also-temporary NEP, with the aim of keeping the worker-peasant alliance together and gradually expanding the size of the proletariat. But without democratic elections, the underlying logic of the process of bureaucratisation remained. Moderate political freedoms were re-introduced under the NEP, but geopolitical isolation and the horrors of the civil war had left the Bolsheviks that still lived with deep paranoid scars, so the Mensheviks and Left-SRs remained banned and there was little in the way of substantive democracy.

This process is often understood as the personal fault of Stalin. He is like a Luciferian figure for many – an original sin that infiltrated the party and filled it out with bureaucrats from the old Tsarist regime. But this is an all-too-easy narrative. Before the 1920s, Stalin was as much a revolutionary social democrat as Lenin was, though theoretically unsophisticated. During the 20s, his centre faction represented not just those bureaucrats who had been absorbed into the party, but a sizeable minority of the pre-1917 membership (including Lenin until 1923). Though possessing an element of cynical autocratic logic, the Lenin Levy and Great Purge were attempts by Stalin and his followers to de-bureaucratise the party, not to subvert it. Its primary targets were Tsarist-era civil servants, not just those opposed to Stalin personally, and they were predominately replaced with peasants and workers.

This attempt, nonetheless, failed. Regardless of the class background of those recruited into the state apparatus, it began to occupy a social position objectively separated from the working class. The incorporation into the party of peasants and workers who had questionable commitments to revolution, or were theoretically underdeveloped, necessitated top-down appointment by the party elite to maintain ideological loyalty and coherence. Ideological lip-service and the cold mechanistic determinism of Marxist-Leninist theory was the result of these objective developments, as the party had no connection to radical working-class self-organisation. Often, it was involved in putting down such organisation. Without this element, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union found itself believing that communism was just a matter of having advanced enough technology – a socialism made of electric lines, concrete-mixers, and churning gears overseen by lab coats. Blaming Stalin is a cop out.

Was There an Alternative?

“How are we to remember them? How do we remember those of whom there is so little left to remember? And above all, with whom do we remember them? To whom do we raise the alarm, who do we warn or turn to for help? Who do we call to in the name of a justice deferred, past due, of zealous partisanship for those the party betrayed? With whom do we mourn the lost, the murdered, the abandoned revolutionaries… With whom to share their loneliness? At least that. At least to offer companionship, imaginary, belated companionship.”

Yesterday’s Tomorrow by Bini Adamczaks

The Bolsheviks faced enormous structural obstacles. Socialism cannot be created in one country. Peasants are an unreliable ally of communism, at best. Isolated, the degeneration of the USSR was inevitable. Many revolutionaries implicitly refuse to accept this, but in doing so they fail to see that every revolution is a risk taken. Guided by Marxist theory and assisted by analysis of objective conditions, this risk is a calculated one. But revolutions, by their nature, expand unevenly. From the perspective of any individual revolutionary, it is always an act of faith – faith in one another’s comrades and faith in the working class. No revolution, not even the one that finally ends capitalism, will be perfect.

But to suggest that the Bolsheviks were simply doomed is to mirror the mechanistic determinism of Marxism-Leninism. The situation of the communist movement, and the decisions it makes, exist in a two-way dialogue with social conditions. This is why it is important for us to understand the Bolsheviks. Could they have done differently? Could they have created communism? Can we? In Australia at least, we don’t have to worry about a worker-peasant alliance. Nonetheless, we can gather two more generic and seemingly contradictory insights from the USSR.

Firstly, that the communist movement must be a vanguard of the proletariat – it should only include those who are committed to fighting for a revolutionary program. If it expands beyond this and invites in reformists, opportunists, or populists, then there are two possible outcomes: conquest of the party by opportunism (as was the case with the German Social Democrats) or bureaucratic elitism. Secondly, the communist movement must win a mandate from the majority of the working class.

The maximally democratic direct rule by the working class squares the circle. The communists must act as leaders of the working class in its war with the capitalists ideologically, politically, and economically. Therefore, we must restrict our membership and engage in constant open struggle. We also need to work constantly to expand our base of support. Democracy, then, is a revolutionary tool; it ensures that those who have not yet – or, perhaps, will not – been won over to communism can represent themselves outside of the party. If we staunchly commit ourselves to workers’ control, there is no need to merge the party with the politically backwards or with the state.

It was possible for the Bolsheviks to democratise after the Civil War. The Left and Right factions in the party were close to concluding a pro-democracy coalition, and the NEP could have continued to have the majority support of the party past 1928.

The Bolsheviks did not do this because they, correctly, predicted that they would be voted out of power. But they underestimated themselves. In fact, this may have saved the revolution. Would they have been massacred? Despite their dread, this was unlikely. Most peasants after the civil war were poor, disorganised, and had no interest in shooting at factory workers. The threat of foreign invasion loomed and suggested the need to industrialise quickly, but how many times can one ask, “what about stopping the Nazis?!” before we find ourselves defending a state that has become an end unto itself rather than an instrument for ending the global oppression of humanity?

The opportunity to forge socialism in Europe and Asia did not die with Luxemburg in 1919. The revolutionary wave continued for another twenty years. The Bolsheviks would have been free to throw all support behind these revolts had they been separated from the state apparatus, rather than backing the capitalists as often as they did the workers in their vain attempts to save the USSR.

In such a position, who knows what may have happened? Would the communists have won the Spanish civil war in 1936? What of Britain, France, Italy, and Germany in the 20s, 30s, and 40s? Would things be different in China? Would we have communism today?

These questions may seem like childish alternate history. To some extent, they are. But the USSR’s failure was not inevitable, despite the structural obstacles. To recognise that and open-mindedly accept that the Bolsheviks failed on their own terms is to open ourselves up to the possibility of our own success. Our failure is not inevitable either. Despite neoliberalism, deindustrialisation, and all the other difficulties, there is a communist future. A future that we can create. Creating that future means understanding our communist past.

You must be logged in to post a comment.