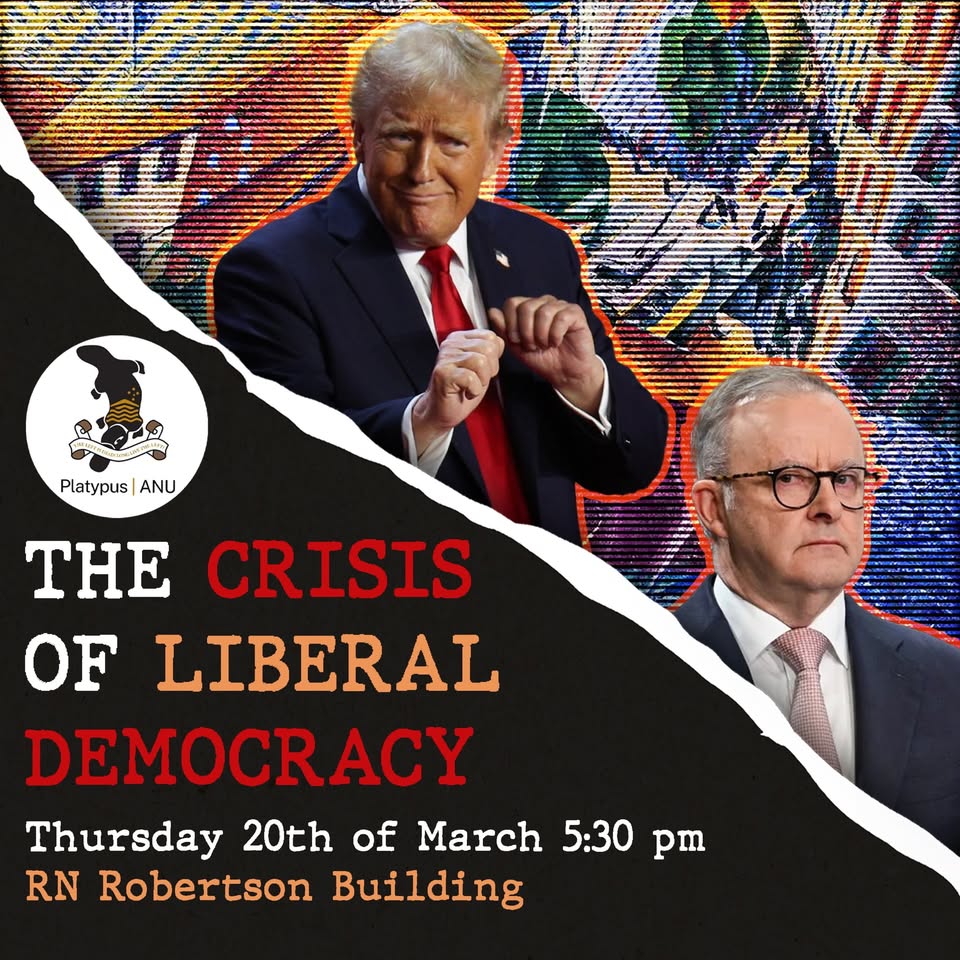

The Australian National University (ANU) chapter of the Platypus Affiliated Society held a panel on March 20th, on the subject of the ongoing crisis in liberal democracy. We publish here an abridged version of the talk given by Mila Volkova of the RCO. Daniel Lopez (Jacobin AU) and Finnian Colwell (Solidarity) were also on the panel.

What do we mean when we address the “crisis of liberal democracy”? I would like to begin with a general theory of the capitalist state, as well as a broad history of it, but I don’t have time. So, let’s focus on the state which we encounter today, the neoliberal one. It’s predecessor, the project state, through its strategy of total mobilisation, swallowed up more and more of society into its administrative and economic apparatuses, and subordinated them to the state’s executive branch, at the expense of the legislature, judiciary, and political parties. In the transition from the project state to the neoliberal state, the economic-administrative apparatuses of the state were basically expelled and given over to global finance. They were then systematically annihilated. The process of financialisation, assisted by computerisation, allowed for a globe-spanning “rationalisation”, whereby finance disintegrated and shuffled around entire sectors of capital for the continued survival of the overall capitalist system.

The welfare arm of the state has lost all its social function, instead existing solely to discipline the working class, whose enforcement is contracted out to the private sector. NGOs and “human resources” have ballooned to make up this yawning hole. The neoliberal state now serves little economic function except as the primary lender, and occasionally stimulus provider, though this role has increased in significance. In a financialised economy, bonds and interest rates play a critical role in supporting the profitability of financial assets, and thus the entire economy. Furthermore, the ideological apparatuses that were formally part of the state, or partnered with it, have declined in prominence. The hegemonic ideology of the capitalists is no longer primarily spread through schools, trade unions, or political parties, but instead through mass and social media. The result is a state in constant anxiety, yet with little capacity to act.

While this transformation certainly defeated the crisis facing the project state; mass workers militancy was destroyed and overproduction was dealt with, the neoliberal state finds itself in its own crisis of reproduction.

The tendency of the rate of profit to fall was not halted, only temporarily reversed and only in certain sectors. Globalisation and the subjugation of production to constant financial oversight was intended to maximise thin profit margins, but it has only accelerated their thinning in the long term. Increasingly complex global markets have accelerated inflation and make market crises more common. This is a self-reinforcing tendency. Low profits in manufacturing, and other “productive” sectors of capital, push investment towards speculation on financial assets. A vicious cycle develops: a high ratio of technology to human labour in manufacturing increases the cost of investment while promising low returns, so capital moves to financial assets, which leads to an under investment by finance and the state in healthcare and education. Thus, the quality of labour decreases, leading to stagnating productivity, and an even lower rate of profit in productive capital, leading to further financialisation. The state can do little but support this process, having been stripped of its capacity to do much else, through the now universal practice of quantitative easing.

Arguably, the ideological state apparatuses are actually at their most powerful in history, in relation to the other apparatuses. Mass and social media have successfully diffused ideological reproduction throughout the entire working class, which has successfully obscured the role of such media, and ideology in general, in reproducing the hegemony of the capitalists. The relations of production have never been so obfuscated. However, this diffusement necessarily brought with it a degree of democratisation. While this has strengthened ideology, it has also destabilised it. This is one explanation for the explosion in subversive “subcultures” such as Queer identification and incel-dom.

We have yet to address the most dramatic cause of the crisis of reproduction – the inclusion of married women into the workforce. The inclusion of married women into the workforce has destabilised the patriarchal mode of reproduction. This mode of reproduction is necessary to capital for numerous reasons: the literal reproduction of the workforce, the outsourcing of care labour from which, though unpaid, the capitalist extracts enormous surplus value, ensuring the continued existence of financial assets (especially the mortgage) through time, and the sustainability of racial hierarchies in the age of mass migration and refugees. In general, the fact that women in the imperial core can generally earn a living without relying on a man, has destabilised the stratification between male and female proletarians, much to the rage of an enormous minority of young men.

All these forces have led to what most call “populism” today. I will not attempt to formulate a general theory of populism, or even a definition, but will rather focus on Trump’s coalition specifically. This coalition is an alliance between suburban middle America, small businesses, manufacturing and extractive capital, and a section of finance capital including private funds, venture capital, and big tech. In the project-state which preceded the neoliberal state, competing sectors of capitalism were balanced through the state’s enormous economic apparatuses under the watchful eye of the executive branch. Since the neoliberal state essentially granted these apparatuses to international mutual funds like Blackrock wholesale, it has wielded them to its own sectoral interests against all others. The ability of this coalition to become conscious of this, and to organise itself to seize power, is reflective of the instability in the ideological state apparatuses (and state apparatuses generally, in fact). These forces specifically have much to lose from the inclusion of women into the workforce. Small businesses are reliant on racialised and feminised wages, manufacturing capital relies on the collaboration of white workers against black workers, and private property generally speaking requires that reproduction be subjugated to private (i.e male) interests, which explains the rabid misogyny of suburbia.

Although this movement resembles fascism, it possessed basically the same class composition, it differs in several key ways. These differences are often obscured by the accusation of “fascism” directed towards the Trump coalition, even if there are certainly fascists within it, so I would like to problematise this accusation. Firstly, while fascism was a reaction against the mass socialist movements of the early 20th century, this cannot be said about Trump. As I have outlined, it is a reaction to different things. Secondly, the Republican party does not mean to build a total mobilisation state. Rather, they aim to reshape the state to guarantee the defence of petty property and privilege. Thirdly, although there may be a mass movement behind Trump, it is not a particularly organised one. Furthermore, despite what liberals may fear, there is not a particularly strong paramilitary wing to this movement, a key trait of fascism. Finally, the fascists aimed to construct a corporatist state that included the working class, balancing classes against one another in support of national projects, whereas Trump has zero corporatist intentions.

Due to the crisis of reproduction neoliberalism has brought on the liberal democratic state, and capitalism in general, this faction’s only option for the conquest of power was through undemocratic means. Winning the popular vote means very little for anyone in the context of a deeply gerrymandered system with extremely low voter turnout. We will likely see an attack on liberal democracy during Trump’s presidency for the same reasons and to maintain this rule. To appease my Platypus hosts, I will add that this is the “rational kernel” of the Trump movement. We are in an epoch where the contradictions of capital are so heightened, that liberal democracy itself seems to have become structurally unsustainable. So far, only this movement has successfully gone about seizing power to finish it off.

What new form of state will arise after liberal democracy? This is an open question. At the very least, we can say that Trump is pushing for the enhancement of the repressive apparatuses of the state, and a reliance on the ideological state apparatuses of the church and mass and social media. On the other hand, China seems to be the only nation-state that avoided the structural pressure that transformed the project state into the neoliberal state, adopting a hybrid sort of model. Although, it seems unlikely that China could successfully replace the USA as global imperial hegemon, and enforce its state model on others, without fundamentally breaking the capitalist mode of production.

We return to the age-old question – what is to be done? While the dominant tendency in the socialist movement currently, economism, was already dubious in Marx and Lenin’s eras, it is certainly more so now. It is obvious that we must rebuild the organs of working-class struggle, such as trade unions, but we can now rely even less on the base tendencies of militancy, struggle, and economic crises to transform economic struggles spontaneously into political revolutions. The negative tendency of capital, arguably Marx’s greatest flaw for not noticing, of disintegration, stratification, and atomisation, has won out over the positive tendency on which the mass workers movements of the past relied upon to unify themselves. The economistic strategy, epitomised in both my comrades on this panel today, has failed for forty years. It is increasingly clear that a-political “base-building” has stalled. Only an organised vanguard, which unites the sects, and which agitates in favour of economic demands for openly political reasons, can rebuild the organs of struggle.

But more than that, in the current era of financial mobility, it is increasingly clear that we cannot achieve even economic struggles without demands for state intervention. Thus, successfully organising around economic demands seems unfeasible without explicit politicisation, and an explicit theory of the state. The question of combining the economic and political struggles imposes itself stronger than before. Indeed, the need to win concessions that supports the self-organisation of the proletariat is greater than ever. Finally, for our economic struggles to be successful in the age of de-industrialisation, our demands must overflow the trade unions and enter the realms of debtor, tenant, consumer, welfare, and household organising, and that we address war and imperialism with more emphasis. Thank you.

Respond on our letters page: partisanmagazine@proton.me

You must be logged in to post a comment.