The so-called ‘Australian dream’, ripped from the U.S consciousness, is a dream of unrestrained consumerism for men, and suburban drudgery for women. Luca Fraillon explains why communists need to push against this idea in order to put forward a revolutionary, feminist program.

Capital, Gender, and the Suburbs

What is the Australian Dream? A large family home, grass mowed in the back garden, a labrador or maybe a golden retriever; two kids – a boy and a girl – an SUV, a tidy nature strip on a quiet cul-de-sac. This mythologised aspiration does not arise from some deep-rooted human desire for privacy, property, or family. Instead, it is borne out of the fundamentally individualising drive of an economic system threatened only by mass collective action, and by the role of the nuclear family in maintaining this. Marx asserted that “ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships”, and it is suburbia that is the ideal expression of domesticity in a capitalist mode of production. As such, gender is constituted and reproduced spatially, the urban/suburban dichotomy serving to maintain patriarchy as the dominant relation of sexes. This is the Australian Dream, which can be re-cast as an Australian Hegemony – the dominant Australian ideology, arising as a mythologised form of the ideal relations of production.

Understanding the relationship between the suburbs, capital, and gender requires an understanding of two important concepts – productive and reproductive labour. Productive labour is that labour which produces capital – what we would generally consider as “work”. Reproductive labour is the labour necessary to maintain a person’s productive capacity – for example, cooking, cleaning, doing the laundry, things which must happen in order for someone to get up and go to work the next morning. This labour is generally unpaid and the brunt of it is almost always borne by women. In Australia, 70% of women spend time on housework, compared to only 42% of men. Labour involved in raising children is another key aspect of reproductive labour, as is reproduction itself, providing a continuing stable workforce for the future – once again, women shoulder the vast majority of this responsibility, spending more time raising children and being the birthing partner in almost all relationships.

Why must reproductive and productive labour be split? Why along gendered lines? The answer here is simply one of efficiency. Reproductive labour is essential to productive labour, however performing it takes time that could be going instead towards producing capital. In separating the male worker’s productive labour from domestic reproduction, more time and energy could historically be spent in the factory/fields/office. As workforce numbers equalise and women take place in productive labour, reproductive labour still remains a feminine domain – women don’t replace housework with work, but instead work what Silvia Federici calls a “Double Day”. To break down the gendered boundaries of reproductive labour would highlight the fact that unpaid labour is required to perform paid labour. It would also require men, who occupy positions of power precisely because of this dichotomy, to consent in overturning it. There is, of course, a class division here as well; bourgeois families instead hire cleaners, cooks, and maids to perform the tasks of reproductive labour.

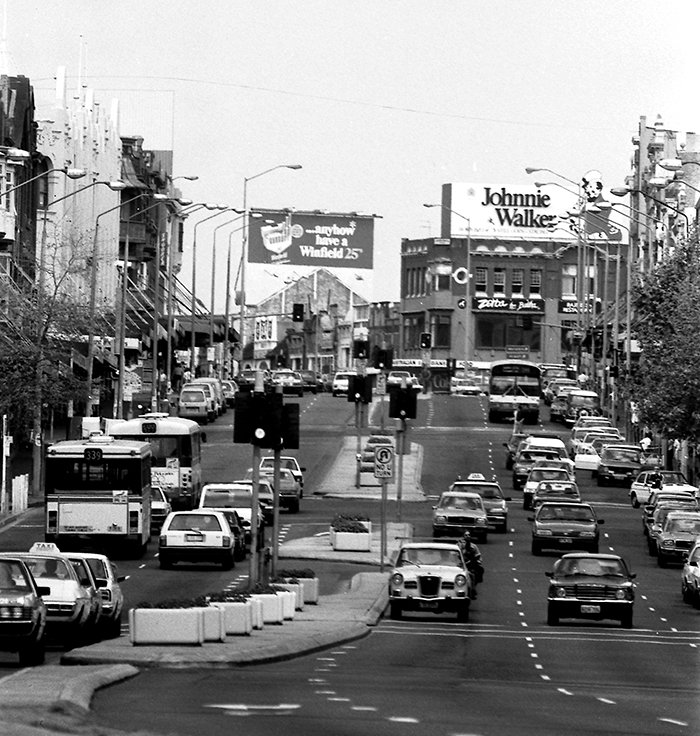

The suburbs have long been recognised as sites by which patriarchal relations are reproduced. Psychologist Susan Saegert described “feminine suburbs and masculine cities” in 1980, noting that increasing the physical separation of home and work served to reify the division between reproductive and productive labour. Saegert and other feminist geographers have consistently observed that the split between the city and the suburbs hides within it a split between reproductive and productive labour; in physically defining the city as a space of “work” and the suburb as a space to “live”, suburbia spatially reinforces the gendered divide between productive and reproductive labour.

The great success of the ‘suburban experiment’ has been its ability to create unity without community; the suburbs serve to simultaneously reproduce capitalist individualism and prevent individual expression. Suburbia exists within this duality and contradiction. It functions, firstly, as an isolating agent, promoting the virtues of owning your own, self-contained home, your own car, caring for your own lawn and backyard. The distance and density of the suburbs prevents the formation of community, with interactions generally limited to immediate neighbours. Property in the suburbs becomes essential to identity. “Your house”, “your land”, separated from the public realm physically by tall fences and legally by subdivision boundaries, the ownership of it as such now fundamentally integral to you as a person. It is in this sense that the suburbs seek to prevent the formation of community, and why they are, in many ways, the epitome of neo-liberal individualism.

Care of the house becomes tantamount to maintaining an acceptable public façade. For housework to be done, however, someone has to be inside the house – something that becomes much more difficult when travelling large distances between home and work. Suburbia, in differentiating physically the house as a feminine domain of reproduction and work as a masculine one, ties suburban life inexorably to the ideal of the “stay-at-home Mother”, a caretaker for property.

It can not be denied that there is unity within the suburbs; the style of house, the style of car, those tidy nature strips on quiet cul-de-sacs. While there is no sense of community, there is a monotony that prevents the establishment of unique identity; the formation of a genuine individuality is prevented, while individualism is held as paramount. Suburbia, as a result, is characterised a tightly controlled set of individuals prevented from forming any collective identity. That is, any collective identity except for that of the nuclear family. The family is seen itself as an individual unit, and one intrinsically tied to property – committed relationships and the arrival of children are two of the largest motivating factors behind home ownership in Australia. The nuclear family is essential in privatising labour, both productive and reproductive, with the aim of providing for your family superseding that of the community, to the point of virtually wiping it out. The prospect of ‘passing down’ inheritance is seen as paramount to living a successful life – just look at reactions to any mention of a “death tax”, no matter whether or not such a policy is even proposed.

What do we really want when we dream of a home in the suburbs? This ideal shows itself to be no more than the ideal conditions for capital accumulation. Suburbia physically weds us to the idea of the nuclear family, spatially separates reproductive and productive labour, and rails at every turn against the synthesis of our “personal” and “work” lives. Fundamentally, it maintains the systems of gendered oppression that best serve the production of capital. This is why the Australian Dream is the Suburban Dream is the Capitalist Dream. Perhaps it is more of a nightmare.

Communists, tear down your fences. You have nothing to lose but your lawns.

You must be logged in to post a comment.