Max J takes stock of pop culture’s “anti-war” film collection to decisively end the debate over whether or not it’s possible to produce an “anti-war film”.

French director and film critic Francois Truffaut may or may not have said that “there is no such thing as an anti-war film”. Many have nonetheless attempted to produce a convincingly ‘anti-war’ film, against the odds. One must imagine Sisyphus happy. There are many reasons as to why it is near impossible to produce a convincingly anti-war film. The main reason, in my view, is that cinema is not capable of conveying the full scale of the horrors of war and brutality in a way that doesn’t turn violence into a spectacle. Standard films, with the trappings of narratives, are by their nature forced into personalised portrayals of warfare: the audience comes to empathise with certain characters, detest others, ‘root’ for a side, so on. Narratives have conflict, which requires an antagonist of some kind. In war stories, the antagonist invariably is the ‘opposing side’ in the armed conflict, especially when the protagonist is a soldier, which is true of the vast majority of war films.

Take, for example, Apocalypse Now (1979, dir. Francis Ford Coppola). While far from being an ‘anti-war’ film (by intention or otherwise), it nonetheless is a critical portrayal of America’s invasion of Vietnam. Despite this, as an audience, we are nonetheless invested in Cpt. Willard (Martin Sheen) and his mission; when he is attacked by Vietnamese and Cambodian soldiers, we are ‘rooting’ for Willard, not the Vietnamese or Cambodian soldiers. We revel in the spectacle of Lt. Col. Kilgore’s (Robert Duvall) violent assault on a Vietnamese village, as American soldiers gun down Vietnamese guerillas and villagers. We are exalted when Willard finally slays Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando) at the film’s climax.

The 2005 film Jarhead (dir. Sam Mendes) is often cited as one of many 21st century ‘anti-war’ films, despite it falling into similar trappings as Apocalypse Now. Swofford (Jake Gyllenhaal), a U.S Marine serving in the Persian Gulf war (1990-1991), is our protagonist, and despite his abhorrent behaviour, we are drawn toward empathising with him. The first act of the film does an excellent job of humanising Swofford, no doubt uncritically adapting Swofford’s own memoir of the same name (from 2003). While Jarhead, like Apocalypse Now, critically portrays America’s invasions and participation in imperialist warfare, just like Coppola’s film, it does so in a way that nonetheless pushes the audience toward siding with the invaders. Jarhead in particular is a ‘shoot and cry’ – initially an Israeli genre of media which took the approach of soldiers ‘regretting’ their military service, but nonetheless being proud of it.

It is a genre which is a mainstay of media across the imperialist world: Australia has its own ‘shoot and cries’ (Danger Close, 2016, dir. Kriv Stenders comes to mind. I was taught screenwriting by one of the writers of that film. This fact is irrelevant), though most of the ‘mainstream’ entries in this genre are from America. While U.S Marines belt out TEENAGE DIRTBAG in Generation Kill (dirs. Susanna White, Simon C. Jones), they slay scores of unnamed Iraqi bad guys. We’re meant to feel bad about the dead Iraqis, but it’s an unfortunate reality that the dregs of imperialist society must fly to other people’s countries to slaughter them for college grants. So too are we led to believe that Anthony Swofford, U.S Marine Scout sniper, is a victim of circumstance. In the first act of the film, he proudly tells his drill sergeant he joined the corps because he “got lost on the way to college”. The ‘terror’ of Jarhead is not the imperialist intervention into Kuwait, but the endless waiting: Swofford goes insane (and we are meant to sympathise with him) because he can’t kill anybody. A pivotal scene in the film, coming at its climax, is Swofford’s first potential kill snatch from him by the air force. In other terms, Swofford is ‘blue-ballsed’ by the US imperialists for the entirety of the film.

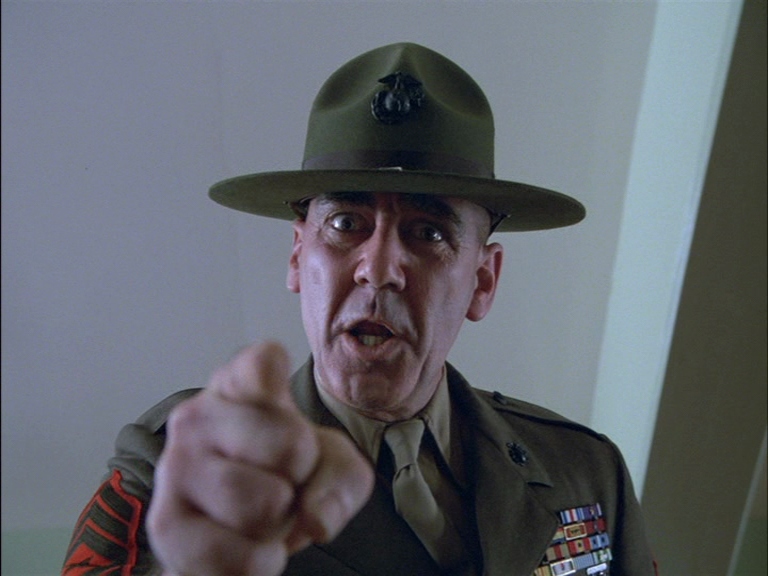

U.S Marines are a particular folk hero of American shoot and cries. Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987) is an infamous entry into the Vietnam war genre of war films, and another cited as an ‘anti-war’ flick. The film’s stark portrayal of U.S Marines as a gang of mindless, racist hooligans did little to deter people from supporting them. In fact, there are many anecdotes of young men walking out of screenings of Full Metal Jacket wanting to join the corps. On the corps, General Pershing once said (allegedly): “the deadliest weapon in the world is a marine and his rifle”. GySgt Hartman, the infamous ball-busting drill sergeant portrayed by the late R. Lee Ermey, proudly tells his cohort of recruits that Charles Whitman (the Texas Tower shooter who slew fifteen people at the University of Texas in 1966) and Lee Harvey Oswald (who may or may not have assassinated President John F. Kennedy in 1963) were taught to shoot good in the marines. As good a sales pitch for joining the corps as any! This obsession with the U.S Marines would continue for decades: Clint Eastwood’s Heartbreak Ridge (1986), Rob Reiner’s A Few Good Men (1992, of “you can’t handle the truth!” fame), and Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July (in 1989) are some of many late 20th century films which helped to build up the mythos of the U.S. Marine.

What about Come and See (1985, dir. Elem Klimov)? A Soviet film, it is cited as a quintessential ‘anti-war’ classic. It is a harsh and brutal portrayal of a young partisan’s struggle to survive the onslaught of Operation Barbarossa. A harrowing film, it nonetheless falls into similar traps as its Western counterparts. While being far from a shoot and cry (its protagonists are the victims, not the perpetrators, of the terror), it is nonetheless a narrative in which the audience is invested in the main character’s (Alexey Kravchenko’s Florian Gaishun) struggle to survive. The antagonists, the invading Nazis, are too villainous and evil an antagonist to view humanely, especially after the numerous atrocities they commit in the film. Come and See thus is less an ‘anti-war’ film, and more an ‘anti-fascist’ film: it is hard to imagine a scenario in which we humanise and seek peace with the Nazis. Even in the closing scenes, where the partisans triumph over the Nazis and the partisan leader Kosach (portrayed by Lithuanian actor Liubormas Laucevicus) prepares to burn them alive, the audience must find it difficult to empathise with the same people who moments earlier pretended to execute Florian for a photo and did a similar mass burning of villagers. Come and See depicts the brutality of warfare and the way it impacts young people drawn into it, war is unrestrained brutality, it is an orgy of violence, and many get into wars with dreams of glory only to find that ‘war is hell’.

Culloden (1964, dir. Peter Watkins) is not a standard film. It follows unnamed TV war reporters as they cover the 1746 Battle of Culloden, in which Charles III Stuart was decisively smashed by the Duke of Cumberland. The film pays special attention to the backgrounds of the soldiers – many of the Scottish and Jacobite soldiers are ‘peasants’ in the Highlander clan system, pressed into service by their ruling class. Many others were present at the battle to resolve disputes between clans (revenge against clans that sided with the British), or out of honour due to being bound to the clan gentry (tacksmen, who ran estates under the authority of a chief). The TV reporter style gives the film a journalistic flair. Our point of view is never named, and we only get occasional commentary from the narrator. Characters within the film, textually men from the 18th century, react rather anachronistically to the presence of a film crew.

Culloden feigns objectivity in the way it portrays the battle, though it does so with a sense of muted sarcasm. It describes the battle as “one of the most mishandled and brutal battles ever fought in England”. Its use of non professional actors, who give ‘amateurish’ performances, helps cement the ‘real-ness’ of the events taking place. Unlike most contemporary war reporters, the unnamed reporters in Culloden are able to interview and cover all sides of the battle: the Jacobites, the British, civilians, etc. It is certainly a unique way of portraying and covering a historical event. It is a film style that Watkins would continue to use for his 1966 film The War Game, which instead covers a nuclear war between NATO and the USSR. The War Game would only be screened to select audiences in 1966, only broadcast publicly by the BBC in 1985. 1984’s Threads (dir. Barry Hines) is a film of a similar genre, though it takes a more ‘cinematic’, narrative approach to the story.

Forty minutes is the amount of time it takes for Charles III’s army to be devastated, both by his incompetent leadership and by the sabres, bullets, cannonballs, grapeshot and bayonets of the British soldiers. Starved, sleep-deprived Highlanders armed with swords and shields charge helplessly against lines of dirt-caked British infantrymen to be aimlessly slaughtered as the reporters record their deaths in black-and-white shakeycam. Just as The Last Samurai (2003, dir. Edward Zwick) was ostensibly a film about feudalism being shot to pieces by capitalist modernity, so too is Culloden a film about feudalism being shot to pieces by the footsoldiers of progress. Violence is gratuitous and ever-present in Watkins’s early films, for which Culloden is the prime offender, being his first full length feature film. However, the violence is rarely a spectacle in Culloden, as precious few minutes are spent depicting the outbursts of violence itself – most of the film concerns itself with interviews of random soldiers, explaining who is who, ‘setting the scene’ of the battle, etc. The battle itself only takes up twenty minutes of run time in an hour long film. Much more of the film’s time, especially after the battle, concerns itself with the battle’s aftermath.

The field of Culloden moor is a circus of misery and suffering. Destitute, press-ganged Scots starve on the field as unwashed Englishmen (and their highlander allies) stew in their own filth. The moor is a wet patch of disease where the battle is a welcomed reprieve from the waiting. Contrasted with the battles in Ken Hughes’s Cromwell (1970), Culloden does not have you rooting for the triumph of either side – instead, it has you despair as the ‘human rents’, Scotsmen who were no more human than sheep were, wait eagerly to be maimed and slaughtered.

Culloden is not content to only depict the events of the battle itself. The battle concludes swiftly, and the British celebrate with an orgy of violence: dying and wounded men are battered to paste on the battlefield, cavalrymen ride down fleeing highlanders and women on the roads to Iverness, British soldiers barge into houses in villages across the area to slaughter Scots at their dinner tables. Warfare is no longer contained to the battlefield, to begin and end with marches and charges: it follows you home and kills you in your sleep. War and violence are inescapable.

Culloden works as an ‘anti-war’ film despite not necessarily intending to be one. It has a journalistic focus on the battle, with the reporters invested in learning the stories of the people involved. The reporters don’t pick sides, though they are sympathetic to the civilians who are slaughtered by British forces, and take an angle that portrays Charles III and his staff as stubborn, while covering the abuse of the British. They are the perfect journalist: they master the balance between objectivity and highlighting the humanity of the people involved. It is ‘Brechtian’ (invokes Bertold Brecht) in the way it pulls the audience out of the narrative to remind them they are watching a film. For this reason, an ‘anti-war’ film must necessarily be a non-standard film. By breaking the chains of a standard narrative, a film can portray conflict, or at the very least its impacts on combatants and non combatants, in a way that avoids turning war and conflict into a spectacle. This is more or less what documentaries and news reports do, or aim to do on paper anyway.

So Francois Truffaut did not believe that anti war films could exist. And neither do I, more or less. But if Truffaut had seen Culloden (1964), I believe he would’ve made an exception.

You must be logged in to post a comment.