Sylvia Ruhl explores the class composition and history of the Australian Greens, and explains why they are not a viable way forward for the Left.

Supporting the Greens is almost the default for those on the Left in Australia. On its face, this is understandable. Since the 1991 dissolution of the Communist Party of Australia, there have been no other large parties claiming to be left-wing to barrack behind. However, this commonsense has proven itself again and again to be a dead-end. For the last thirty-two years of their existence, The Greens have functioned as nothing more than a graveyard of social movements, most notably the environmental movement. In doing so, they have diverted the precious time and energy of left-wing activist youth into a pointless electoral project.

Wait, so who are the Greens, really?

The class position

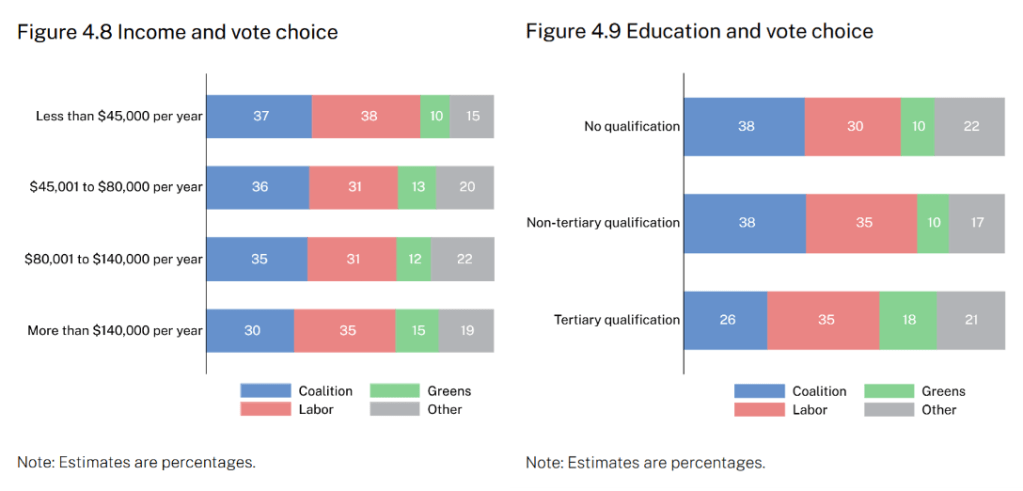

The Greens voter base is comprised, for the most part, of downwardly mobile middle-class professionals. Some in the party say that their support base has a substantial working class element. However, the voter-income data that exists shows the opposite, with Greens voters being more likely to have a higher income, and more likely to have a tertiary level of education (Graph 1); clear signifiers of a middle-class party. These same supporters are the university-educated young to middle-aged people who “lost out” following the decline of the post-war Consensus.

These young professionals were sold the promise that if they went to uni and worked hard, they would live a “successful” life. Of course, that idea of success is confined to working a white-collar job and owning a house in the inner-city, bought on their own income. Ultimately, they simply want these things to be possible again. However, we can never turn back the wheel of history, and nor would we want to. The Post-War Consensus was financed by the exploitation of the Global South; Australia’s ventures in Vietnam for example were by no means disconnected from our economic prosperity that enabled such “success” for much of the middle-class. The Greens, as a party that pursues redistribution within the borders of one country, cannot by any means be considered socialist; they are a thoroughly bourgeois party devoted to the capitalist order, even if they may wish to change it.

The patrilineal, ideological lineage

The class position occupied by the Greens as the socially liberal, party of the professional petit bourgeois is not novel in Australian political history. Before their early electoral successes, their position as the party of the urban petit-bourgeois was occupied by the Australian Democrats, a moderate splinter from the Liberal Party. The early Greens would gain a significant portion of its early membership from the Democrats, with many jumping ship as they took the latter’s place. The Democrats themselves were descended from earlier Liberal Party splits, such as the Liberal Reform Group, and the Australia Party, which formed in 1966 and 1969 respectively.

The first and most obvious distinction between the Greens and their progenitors, is their overall stable level of electoral success nationwide over a span of three decades. This is partly because those earlier parties did not exist in a time when the social pact was breaking down.

When young, middle-class professionals increasingly face housing precarity and fewer professional employment opportunities, a party for their own class has a far greater basis for success. This is what underlines the Greens “pro-renter” and “pro-mortgage-holder” policies; not that of a cost-of-living relief for the working class, but as a reflection of the desire of the middle-class urbanites who too, now struggle with these pressures.

The matrilineal, movement lineage

This degree of “success” of the Greens would not have been possible without their continued incorporation of left-movements. This has been the case from the get-go, with the name of the party itself being an enduring legacy of this appropriation. The Greens emerged from the environmental movement of the 1980s, with which they would for a time become synonymous with. The first initial grouplet that would form what would become the Greens was the United Tasmania Group and was founded in 1972 by environmental activists (including future Greens founder Bob Brown) campaigning against the construction of the Lake Pedder Dam.

The single, unified party now known as the “Australian Greens” was founded by a federation of state-based Green parties in 1992, with politics wildly differing within and between the various sections. The sections themselves were a motley of conservative Tree Tories, environmentalists, anarchists, and former members of the Communist Party.

The incorporation of the environmentalist movement from whence it emerged is what drove the Greens’ initial success and growth. It would then ride this wave into usurping the Democrats as the party of the petit-bourgeois liberal-left, who had failed to capture the environmental movement in the same manner.

Furthermore, the incorporation of hardened cadres left without a political home after the fall of the Communist Party of Australia helped the party’s growth. This incorporation of socialists has had the effect of severely limiting the ability of an independent working-class politics to reemerge. Following the dissolution of the CPA, former members attempted to regroup the socialist movement under the banner of the New Left Party (NLP). The NLP was a flop, partly because much of the needed resources and cadres left for the Greens.

The contradictions inside this class-movement alliance

Although socialists on the party’s left-wing support making the Greens a mass working class party, the party on the whole is aversive to getting involved in union work. In its place are reactionary efforts to ‘defend the community’ and support small business-owners. This lays bare that the basis of the Greens support is ultimately based in the urban small business owners of the major cities. Any worker who joins such a coalition ultimately subordinates themselves to their bourgeois program.

Because of this, the Greens have effectively acted as a graveyard for left-wing movements. The party does not advance the Left, but rather, binds it to a reformist program that refuses to challenge the capitalist order. Most recently, we have seen this with the Palestine solidarity movement. Over the last few years, solidarity with the Palestinian struggle has grown substantially across the Australian left, including in the Greens. The Greens now make vague calls for Palestinian liberation without specifying if this means a two-state solution, or the necessary disestablishment of Israel.

Regardless, they make no mention of Israel’s role as a base for US imperialism in the region, nor do they denounce the Arab regimes as Western collaborators necessary for Israel’s genocide. The only road to Palestinian liberation is to sweep aside the imperialists through a regional wave of socialist revolutions. The Greens fundamentally cannot promote this anti-imperialist program as a party that upholds capitalism.

We therefore can’t expect progress to come from the Greens on the question of Palestinian liberation. Such contradictions between the liberatory movements they incorporate, and their petit-bourgeois base doom the Greens electoral project to inevitable failure and disintegration.

Wait, why is their electoral project doomed?

The most simple reason for a leftist to write off the electoral road offered by the Greens is that it is impossible for them to form government. The narrow, middle-class support base of the party limits their only substantial support to small pockets of bohemian suburbs (their support even in these few areas is by no means stable, as we will see later).

Many in the party have expressed a desire to connect with the working-class and see their cost-of-living policies alone as a valid way to win over the workers. To win in the working-class suburbs, they would need to become a mass party of workers, meaning they would have to work within the unions, and the workers movement. As mentioned above, they are a petit-bourgeois party, and as such cannot meaningfully do this.

Were it possible for them to become a mass workers party, it would mean abandoning the petit-bourgeois for an explicitly working-class, and class-conscious program. While at such a hypothetical point they can easily gain more success, they would cease to be the Greens.

A Long, Steady Ascent, or Professional Losers? (1992 – 2022)

After federating in 1992, the Greens would, with ebbs and flows, increase their elected representation in the federal Senate over a period of three decades. In this time they would gain a few lower house seats here and there in the various state Parliaments. Greens electoral success seemed to be growing, albeit at a glacial pace. This supposed growth was seemingly vindicated by the 2022 “Greenslide”, in which three candidates for seats in inner-Brisbane were elected to the federal Parliament’s Lower House. This was the party’s greatest electoral success to date.

The Queensland Greens Disaster of 2024

Things seemed to be on the up, and it was anticipated that the wins in the federal election could be replicated. In the 2024 local and Queensland state elections, seats were targeted based on whether they overlapped with the electorates they had won in 2022. They spruiked a goal of surging from one to six seats on the Brisbane City Council. They barely edged out a second seat.

Demoralised, but seemingly not humbled, they were still keen to set lofty goals for the following state election in October. With only two sitting state MPs, they would publicly state their goal of winning up to ten(!) seats in suburban Brisbane. They went on to lose one of their seats, and barely retained the other.

There are no two ways around what happened: it was an unmitigated disaster. Unfortunately, even a resounding defeat cannot stop some from teasing out optimistic conclusions; some members are eager to tell their detractors that internal polling has found that some forty percent of voters thought(!) about casting a vote for them. This thought process can be summed up in one word: cope; you would need to be in denial of reality to think this analysis is in any way profound.

And how did this happen?

There have been a multitude of reasons given for the poor showing at this year’s elections. The right, both in and outside of the party, blames the party’s expressions of solidarity with Palestine. It is undoubtedly true that some have changed their vote on this basis, and this reflects the contradiction of incorporating an anti-colonial movement into a party of small business owners. It is likely the party’s right-wing will use this as a basis to intensify its struggle for power.

Others have switched their vote thanks to progressive policies by the Miles Labor government such as 50 cent public transport fares, and the disproportionate focus of Labor electioneering on Greens-held seats. Most of these are probably to some extent true in the context of this year’s elections. Though, ultimately, the party’s internal contradictions are what prevent it from cohering a stable electorate that lasts more than one election cycle.

Socialists in the Greens are dedicated to building a party of the Left that can fight for workers. Their organising efforts therefore need to be directed into a party that can carry out this fight, and win. If the Greens have already reached their maximum possible level of “success”, these members need to ask themselves the question: “What is the point in being here?”

Is there an alternative?

The party of the Left needs to be the revolutionary party of the working-class, that is, the Communist Party. This is due to the class’s unique, historical role as the revolutionary class. It is the global, heterogeneous class that constitutes the vast majority of the world’s population. When acting as a class-conscious agent under its own party, it is not mired by the nationalist, profit-driven interests of small business owners that parties like the Greens base themselves in.

To build such a party, we need to build workers’ power. This power must be built wherever the workers are: the workplaces, the unions, the working-class suburbs, and the universities. Of course, the party should not limit itself from including members of other social classes, but the basis of its power must be in the proletariat.

Leftists in the Greens are pessimistic, and lengthening their stay will only continue to bind the socialist left to a defeated, emaciated electoral project. The way out is simple: the Left must abandon opportunists of all stripes and begin the long work of rebuilding the Communist Party in Australia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.