Anthony Furia reflects on the current nature of the fight for a Democratic Republic in Australia.

The fight for a Democratic Republic in Australia has, historically, been absent from political relevance. Some may point to the democratic aspirations of the Eureka Stockade, yet such an instant of struggle was, while democratic, certainly not Republican. Other moments, such as Howard’s plebiscite for a Republic, were thoroughly republican, but bourgeois republican – the furthest thing from democratic! All things considered then, the state of the struggle for a democratic republic currently is a continuation with its history of political irrelevance. Australians care less about republicanism than they did 30 years ago, and 30+ years of a splintered sectarian left has rendered the demand for a democratic republic even more impotent than the demand for a bourgeois one. What we must attempt to understand, in the face of overwhelming popular apathy and a continued abandonment of the struggle for democracy by the left, is precisely why the struggle for a democratic republic remains so marginalised – what is presenting its flourishing? What part does the socialist movement currently play? What can we do to popularise this struggle? This is not so much as an autopsy of the current state of things – that would require more depth, and imply the movement for a democratic republic is permanently deceased – but a brief sketch. A drawing out of the factors involved in where this world-historic struggle has found itself today, and a scratching out of what the next steps in this struggle must be.

The Bourgeois Republican movement is the first subject of our query, or would be if it could be found in any serious, substantial capacity. It seems that such a movement has, for the most part, collapsed in on itself into vague sentiment and political apathy. With Australian capital either completely silent on the question of a Republic, or profoundly and vocally anti-Republican, and with the Australian population demotivated and demobilised since the failure of the 1999 referendum, Canberra has no reason to even entertain the question of Republicanism. Albanese, the muddle-headed incompetent that he is, has ‘put on hold’ plans for a Republican referendum – paying lip-service to the movement, and little else. The Australian Republic Movement has been hopelessly NGO-ified; a collection of fools and ghouls in symbiotic relation with the subdued body of “green and gold” bourgeois nationalism. To say anything more about the bourgeois republican movement seems to be a waste of words – they are inept, incapable, and relegated to the political sidelines with the occasional nod in their direction from the real figures in high politics.

The reality is that the Australian national identity, Australian nationalism, is perfectly comfortable within the shade of the British Empire and in embrace with the British monarchy. In fact, maintaining these ‘cultural’ and formal political ties with the ‘West’ is, whether they recognise it or not, a benefit for those who identify with the Australian colonial project and state. In an extremely rare stroke of clarity, Huntington was right when he stated that Australia was “torn” between West and East. Without political and economic ties explicitly to the West, Australian nationalism loses its very basis as a western nationalism, a colonial nationalism, an imperial nationalism. Could it reshape itself in the absence of these ties? Most definitely. Is the Monarchy the only way to secure these ties? Certainly not. Yet it remains a convenient way to secure this national project – and, in the absence of a major, concerted shift in the character of Australian national identity, there is no fundamental self-interest from the ideological demagogues of the Australian bourgeoisie nor from Australian capital itself to pursue a Republic. The movement is thus useless even in its own pursuits – it is nothing, and will remain nothing without some great reactionary revival of Australian national republicanism (may it never come). The only anti-monarchy sentiment from Parliament with the King’s visit was Lidia Thorpe – and such statements came from a place of progressive Blak nationalism, rather than any preoccupation with the democratic struggle as a broader project of emancipation.

But we have talked enough about bourgeois republicanism – it is, even in its ‘best’ form, a malformed version of only part of what we demand in the struggle for a democratic republic after all. Instead, we shall turn our critical eye to the Australian public as such, and their role in the current state of the struggle for a democratic republic. That role is almost total disengagement – apathy, disinterest, and indifference. Those of a more progressive inclination will agree, in vague terms, with the notion of an Australian Republic (as will some of those with a reactionary nationalist inclination) yet they remain disinterested in the struggle for it – let alone the struggle for a democratic republic. The unfortunate truth is, post-1999, the average Australian does not care about the democratic struggle – they are not stupid, nor ignorant, for this lack of investment; there has really been no struggle for them to care about in the first place! As communists, this lack of engagement should not dishearten us in the slightest – almost all of what we advocate is wildly unpopular and has been for decades, and we understand political consciousness is not spontaneous, but shaped by education and tested in struggle. Is it any wonder that, at this current moment, the Australian populace writ large is disengaged with the struggle for a democratic republic (or even a bourgeois republic) when there is no agitation around it? When education and struggle are absent?

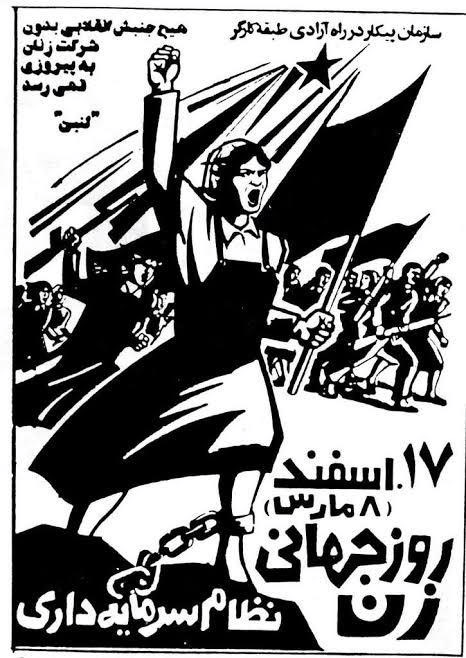

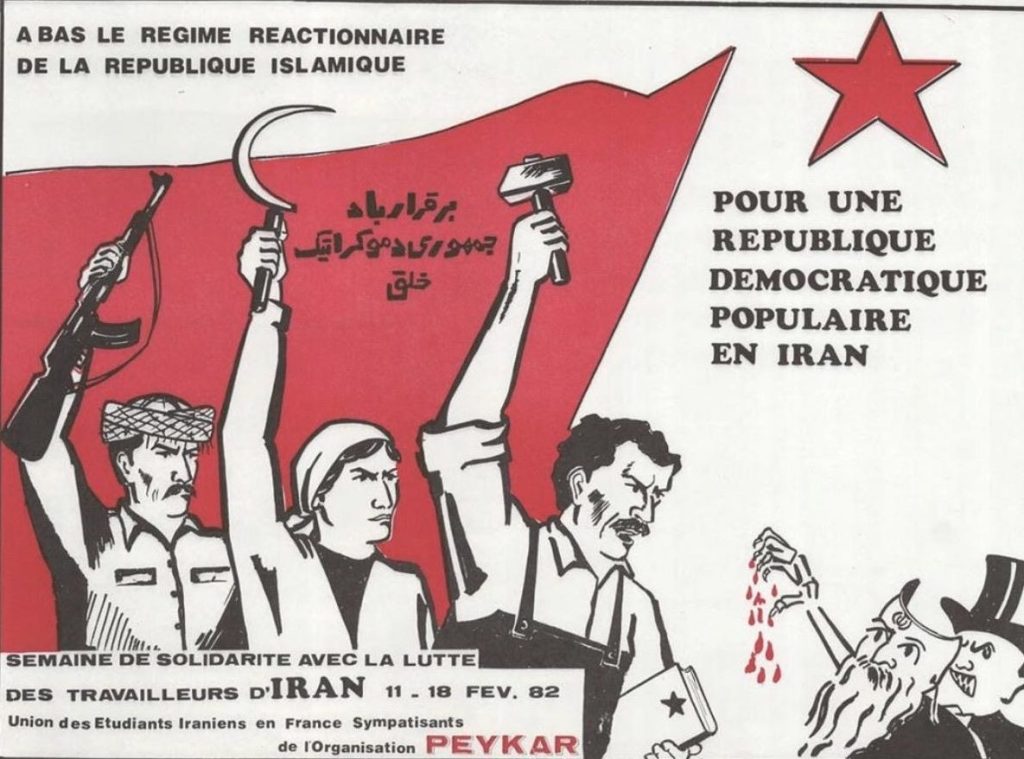

So our attention must turn to those who should, in theory, be responsible for this agitation, for raising the demand for a democratic republic, and ask ourselves; what have they been doing instead? Who is this elusive subject, this (theoretical) carrier of the banner of democracy? The socialist movement. Where has it found itself? Far away from democratic struggle – as if it is organisational repellant. Perhaps an example is in order. Recently, the RCO coordinated speak outs in Brisbane and Melbourne against the King’s visit and in favour of the democratic republic. To their credit, the Spartacist League of Australia endorsed the event in Melbourne, and committed time and resources to it. Other sects in the socialist movement either failed to respond completely to outreach, declined, or stated their willingness to attend before utterly failing to show up in any capacity (with the exception of perhaps the CPA-ML, although they didn’t make themselves apparent).

Certainly, one event (by a frankly middling, in terms of membership and influence, sect in the socialist movement) can’t be extrapolated to ascertain the very nature of the struggle for a democratic republic today – but it isn’t simply one event. It is a consistent pattern of ignoring, minimising, and downplaying the importance of the democratic struggle – of sidelining it, of utilising it unproportionately and only in service of the reproduction of the sect. The slogan of a democratic republic, indeed in almost all respects the question of democracy (other than the inane protest chant “this is what democracy looks like” – which it isn’t, democracy is far more than organising a single-issue sect protest) no longer occupies central, or indeed any stage, in the socialist movement’s imaginary.

Why is this the case? Why has the socialist movement neglected this struggle? There are many reasons – but the primary one is the fractured nature of the socialist movement itself – its existence as sects, as opposed to a communist party, and, as consequence, the historical undoing of the merger between the socialist movement and the workers’ movement. In a splintered movement detached from the workers’ movement as such, the standard sect will continue to operate as if it itself is the genesis for the party. Yet it is small, it is competing with other groups who see themselves as the rightful inheritors of Marxism’s mandate, and it is unable to connect with the workers’ movement as a party would. As such, shortcuts to grow membership, to outcompete other groups for the thin layer of the population who radicalise each year, to attempt (in vain) to merge with the workers’ movement as such, the modern sect finds itself increasingly susceptible to a range of so-called ‘strategies.’ Many of these involve the essential abandonment of the democratic struggle – they may centre almost entirely on economic demands, may emphasise the immediate plight of specific sections of the working class over the project of scientific socialism, or may seek to tail spontaneous social movements as they emerge – scraping together the membership to reproduce itself, and an often schizophrenic collection of theoretical positions to justify this existence separate from all other groups. Were a sect to fall into these trends – which some would call economism, workerism, and tailism – they would have almost no immediate political reason to propose a democratic republic, or to carry out democratic struggle. Unless it spontaneously becomes in the (economic or otherwise) interests of ‘the working class,’ or a social movement emerges centred on abolishing the monarchy/the Senate/making bourgeois democracy more ‘representative’, the sects have no material motivation to wage democratic struggle as such. They are impotent doubly so – insignificant in size and influence, and bound to a working class that will not spontaneously achieve self-consciousness, waiting for it to do exactly that. Resources are scarce enough as is on the socialist left, why waste them on some political demands that don’t immediately inspire, or provoke spontaneous reaction in the Australian population?

Why does this impotence matter? Because politics matter. Because the struggle for democracy is the struggle for workers’ power. Because we cannot rely on economic demands, or social and cultural issues of the day, to cohere an alternative pole of power, to destroy the bourgeois state itself and seize power as such. Because the democratic republic is a representation of the form proletarian state power can take – and implies as such in its definition.

Yet the sect remains useless, as the socialist movement remains useless, based on a fractal splitting and division which is yet to find its resolution. What solution can there be? Well, in the long-term, the solution is the programmatic unification of this socialist movement into a communist party – and this party’s merger with the workers’ movement as such. Such steps would infinitely increase resources and capacity for struggle, democratic or otherwise, and clarifying the importance of democratic struggle as such. In the absence of a spontaneous miracle, the immediate goals of communists are then to make this argument – to make the case for partyism, for the communist party, to themselves, to each other, to the socialist movement in its entirety. To push relentlessly for this unification, for a program for the communist party, and to win. Simultaneously, the RCO will continue to wage democratic agitation where possible, and continue to make the case for a democratic republic openly and proudly. We invite all other sects to do the same, and welcome their contributions to reviving this struggle existentially important to communism.

You must be logged in to post a comment.