Comrade Mila Volkova reflects on the evolving ideas of Marx on the Democratic Republic.

Most Marxists today, when asked what working class rule will actually look like, quite stubbornly refuse to answer. In Marx’s early writing, he was like this too. He avoided the question of political form quite explicitly, as in the actual constitution and rules of the revolutionary state. He argued that the particular form of workers’ rule must emerge from objective material conditions rather than the subjective arguments of intellectuals.

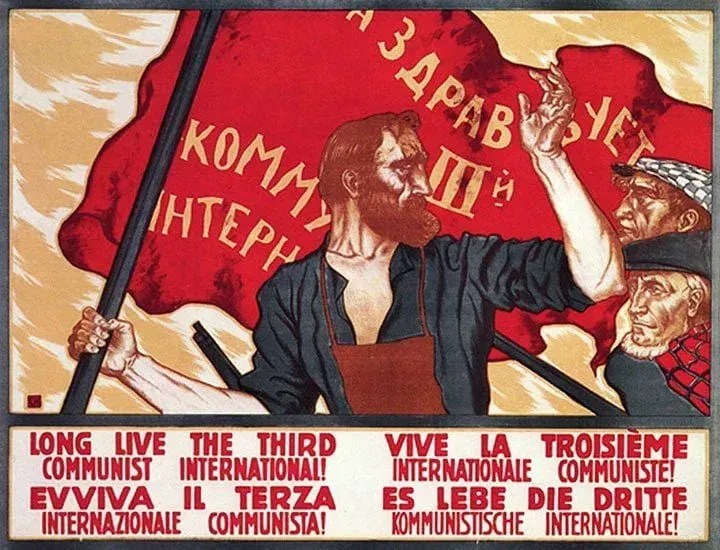

With the uprising of Parisian workers in 1871, Marx’s views on this shifted. Marx did not exactly declare the constitution of the Paris Commune the absolute and one-and-only form that the proletariat-in-power must take. Nonetheless, Marx argued that the political form of the Commune was an expression of the political content of the working class. Despite its flaws, which Marx pointed out, it put the workers in power. It expressed the character of the working class as an international class, whose aims are to abolish capitalism.

Why did Marx do this? What was the Commune really like? What actually changed in Marx’s thought because of the commune? Why is this important for Marxists today?

The Manifesto

The culmination of the pre-commune period of Marx’s ideas is the Manifesto of the Communist Party, which formed the foundation of Marxist thought. We find familiar notions here where Marx outlines, in simple terms, the contradictions inherent to the industrial mode of production. This mode of production has, or is in the inevitable process of completing, the reduction of the entire world into two opposing classes – the bourgeoisie (the owners of private property and the means of production) and the proletariat (those who perform labour and own nothing but their capacity for labour). This mode of production, and the revolutions enacted by the bourgeoisie to establish it, have swept away all previous classes, status relations, and privileges.

However, in doing so, it has unified all the past working classes into one single class with one enemy. The industrial mode of production, by taking the means of production away from the petty producers, has turned production into a process encompassing all of society rather than individual endeavour, a contradiction with the centralisation of private property under capitalism. Marx also outlines other contradictions, such as the tendency of this mode of production to overproduce and then crash.

Essentially, Marx’s thesis is that capitalism spells its own doom by socialising production to the extent that private ownership becomes irrational and unnecessary, and creating a class (the proletariat) that then seeks the abolition of private property. This process, if achieved, would be the proletariat abolishing itself. Thus, Marx claims that the proletariat is the only revolutionary class, as it is the only class that seeks its own destruction, and the destruction of all classes, rather than its perpetuation as a class.

Not only does the proletariat seek its own abolition, but the conditions of industrial production develop its capacity to do so. By destroying all past distinctions between workers, by confining them all into factories where they can develop ideas collectively, and by expanding this mode of production across the entire planet – capitalism has given the workers the chance to organise collectively in a manner previously impossible.

For Marx, both as a necessity, and as a natural outcome of the relations of workers in the system of production itself, emerged the Communist Party. The Party arises from the most conscious sections of the proletariat and aims to represent their interests as a whole – as in, agitating for a revolution which overthrows the bourgeoisie and installs the proletariat to ruling political power. From there, the proletariat can abolish itself by taking management of the entire economy away from the bourgeoisie and into the state under a “common plan”. As Marx argues that states are simply an extension of enforcing class rule, the revolutionary state led by the Communist Party will “wither away” with the destruction of the bourgeoisie, and thus the proletariat, as a class and thus the destruction of all classes.

However, Marx makes no attempt to describe the specific form that this revolutionary state will or should take, and instead focuses solely on its content, the qualitative relationship between the proletariat, the Communist Party, and the state. The Party is the culmination of the interests of the working class, the revolutionary state is a tool for abolishing classes, and the Party works as a vanguard for the proletariat within the state. The Manifesto does contain Marx’s guess at what most communist parties will seek to immediately achieve on conquering power, setting the stage for later Marxist’s minimum-maximum style of party program (where “minimum” is the immediate aims of the party in power and the “maximum” is the full achievement of communism)., but this is as specific as it gets. Prior to the Commune, Marx posits no vision for what form the constitutions of proletarian dictatorships should take. Indeed, Marx explicitly argues against doing so: political forms should arise from the material conditions of a given situation, which are context-dependent, rather than the idealistic imaginations of socialist thinkers.. Essentially, discussing form is idealism, it isn’t a materialist matter of discussion for Marx at this stage.

Marx in Transition

In The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Marx gives a historical play-by-play of the revolution in which Louis Bonaparte subverted the newly created national assembly and installed himself as emperor of France. Although Marx’s commitment to avoiding discussion of political forms remains, he points out how the form of the new republic allows the bourgeoisie to maintain power. He argues that the bourgeois form of government is characterised by constitutionalism (the raising up of some laws above others, unchangeable by simple majority vote), the separation of powers (the division of the state into its legislative and executive functions), and limit of the voting franchise. These are the mechanisms by which the bourgeoisie limits democracy and the influence of the proletariat over the state. Constitutionalism inhibits democracy by blunting the extent to which popular majorities can remake the state and claim power for themselves against bourgeois factions or parties. This allows the bourgeoisie to rule despite lacking majority control of the state. Marx saw the separation of powers as mimicking royal prerogative, allowing the apparatus of the state to avoid direct democratic accountability either through ministerial responsibilities or by combining executive power into a president.

Underlying these critiques is a view that true democracy is the representation of the whole against the particular or minority: constitutionalism allows certain laws to continue existing even if the majority disagrees with them, and the separation of powers confines certain state functions to particular individuals with particular interests. This is linked with Marx’s claims that the strength of the working class, and its vanguard in the communist party, is its unifying common interest as an entire class, in contrast with the previous social order of privileges and interests which divided the working classes. Indeed, Marx makes the argument that the bourgeoisie are using the vestiges of old aristocratic forms of government to continue its rule.The bourgeoisie had realised that cementing its own rule against the aristocracy would, in fact, allow the proletariat to destroy it soon after .This is the first time Marx makes a connection between the content of the proletariat as a class and the political form of the state as a tool of class rule. The bourgeoisie protects itself using certain political forms to countervail the inherent character of the proletariat and maintain control of the state. Perhaps the proletariat would have to do so also?

Following this argument to its conclusion, Marx makes the first beginnings of a vision for the political form of the social revolution out of his rejections of the political forms of the status quo. Whereas Marx left out the specifics of the seizure of state power in the Manifesto, here Marx argues that overcoming the bourgeoisie requires not just the seizing of control of the pre-existing state apparatus, but also “smashing” it. The political forms of bourgeois rule must be replaced rather than simply deployed. However, Marx does not yet formulate what exactly should replace this apparatus once smashed. That is, until the Commune.

Marx and the Commune

Whereas previously Marx refused to envision a positive form of the social revolution, Marx finds the definitive “positive form” of the social revolution in the Commune. In The Civil War in France, Marx engages with the specific form of the constitution of the Commune and congratulates the communards on the forms of their revolutionary state: a single popular assembly combining the executive and legislative functions, the abolition of the bureaucracy and popular administration, and yearly elections of recallable delegates with bound mandates. In this model, Marx finds the negation of the political forms of bourgeois rule which he previously criticised.

In the article Revolutionary Commune, Korsch makes the argument that none of this is really a departure from Marx’s previous views: Marx remains committed to the formlessness of the revolutionary state and opportunistically “usurps” the Commune as a propaganda tool. If one reads Marx as advocating for the Commune as the definitive positive form of the social revolution, then Marx is in contradiction with the rest of his own work after 1871. Indeed, one of Marx’s letters seems to completely disavow the Commune, arguing that it was never going to succeed and that it should have sought to create more favourable conditions for a revolution of the whole French nation later.

I think Korsch approaches this development in Marx’s thinking from a backwards-justifying perspective. In Revolutionary Commune, Korsch’s primary aim is to criticise what he sees as a concerning growth in Marxists fetishising the form of the Commune and the Soviets as a necessary or sufficient condition for a revolutionary state. In doing so, Korsch aims to justify these criticisms by interpreting Marx as fundamentally agnostic and explicitly against any discussion of the usefulness of this or that form of revolutionary state. However, I believe he reads this into Marx rather than Marx being truly so stubborn on this matter. Marx had a history of supporting the sort of direct democracy that occurred in the Commune, so it seems unlikely that he advocated for it from a purely strategic perspective. Similarly, Marx’s letters after the Commune present a more nuanced analysis of it, as Marx also advocates for revolutionaries taking advantage of the “accidents” of history, in the manner that the Commune did, and that the time will never be perfectly calculatedly right.

Korsch’s argument relies on a reading that Marx has deliberately downplayed the federalist character of the Commune, which is in contrast with Marx’s sharply centralist views. Therefore, Korsch argues, Marx must be writing strategically in supporting the Commune. However, I believe that Korsch misses that Marx’s post-Commune writing is a development consistent in both his past and future views. While it may be true that Marx downplays the federalist character of the Commune, Korsch overstates exactly how federalist the Commune really was. Ironically, Korsch making so much of the Commune’s constitution is a sign of the sort of fetishism that he is criticising! In either case, this does not lead to the conclusion that Marx remained just as agnostic on the question of political form as previously – rather that criticism of federalism is perfectly consistent with support for the Commune’s constitution.

Workers in the Commune, rather than sending representatives every four years or so with discretion to make decisions on the proletariat’s behalf, sent yearly delegates with explicit instructions who could be recalled at a moment’s notice. Korsch is correct to argue that this constitution on its own does not make a state a proletarian dictatorship, but Marx never implied this. Marx pointed out how this form allowed for the revolutionary initiative to remain with the workers themselves. This contrasts with the bourgeois republican form, in which workers express themselves in elections which he describes as singular and temporary events – a “sensation” and “moment of ecstasy” as opposed to genuine devolution of power to the masses themselves. The bourgeois form is conducive to a reactive, passive proletariat whereas the Commune form is conducive to a proactive and revolutionary one. While Marx remained open-minded on the political forms of the revolution as previously, which Korsch is correct in arguing, his support for the Commune’s model clearly demonstrates newly developed views as to what forms of revolutionary state would likely arise out of the conditions of a revolutionary situation and which, Marx argued, would aid the further development of those conditions.

Marx also makes a critique of hierarchy within the state administration, where bureaucrats are chosen by higher-ups rather than elected at the local level, which Marx supports on the grounds of smashing the bourgeois state and giving power to the proletariat. After the Commune, when Marx argues that the revolutionary state is the “lever” of action for overthrowing the bourgeoisie, he points to the Commune’s constitution as a political form in contrast to both the “break up” of France and the disingenuous “devolution” pursued by bourgeois republics, where localities remain subjugated to the central government and simply act as organs of its policy. Korsch’s reading that Marx downplays the Commune’s federalism is correct in so far as Marx ignores that the Commune’s constitution advocated for voluntary association between free communes, but incorrect in so far as that same constitution advocated for continued unity of the French workers on a national level, and in the reality that some communes sent delegates to Paris and that efforts were made to form a national revolutionary government.

This more charitable reading views Marx’s support of the Commune’s constitution as developing out of his opposition to rule by the particular over the whole and of the role of bureaucracy in alienating the state from the masses. Marx’s analysis of how the Commune smashed these political forms and replaced them with one serving the interest of the proletariat is not so out of character that one must, as Korsch does, enforce a reading of Marx claiming that the Commune is the be-all-end-all social revolutions and then imagine that such a claim is disingenuous. Marx justifies his support by arguing that the specific political form of the Commune was particularly conducive to a socially revolutionary content and that, consistent with his previous views, the political forms produced by the material conditions of a revolution propels the content of the revolution in an increasingly revolutionary direction. Essentially, according to Marx after the Commune, while this or that form will not make a state revolutionary by definition, not all forms are created equal, and some are better than others at producing a more revolutionary content. Marx proudly advocates for the political form of the Commune while remaining as flexible as ever.

Conclusion

While the Commune does not exactly represent a turning point in Marx’s views, it certainly developed them in new directions. The actual, albeit brief, existence of a proletarian dictatorship shook Marx out of his committed refusal to speculate on the political forms of the revolutionary state. Instead, Marx engaged with the Paris Commune’s constitution as a concrete expression of the material conditions that he was waiting for, articulating how it arose from the proletariat’s inherent content as a class and its emerging need to smash and replace the old state to achieve its destiny.

While he remained committed to the basic theory that the particular political form of a revolution will simply emerge from its content, he developed more nuanced views as to what these political forms can and should be as the world changed around him.

What can communists today learn from this?

Firstly, we must not be so stubborn on the question of the political form of workers’ rule. We shouldn’t fetishise this or that form of historic proletarian rule, but neither should we ignore history. History is rich in insights on this topic. If Marx’s views on this changed with the times, the least we can do is look to the past.

Secondly, Marx provides us with a method for analysing workers’ rule. What keeps the initiative with the masses? What propels the masses to go in further and further revolutionary directions? Which political forms express the political content of the workers as an international and united class?

You must be logged in to post a comment.